Pope Boniface VIII’s Textile Donations to Anagni Cathedral

1. Introduction

2. The paraments in opus cyprense (second quarter of the thirteenth century, possibly Cyprus or Sicily)

3. The paraments in opus anglicanum (late thirteenth century, England or France)

3.1 Cope with scenes from the life of the Virgin and the childhood and Passion of Christ

3.2 Cope with the martyr saints

3.3 Chasuble (former dalmatic) with scenes from the life of St Nicholas

4. The antependium with enthroned Madonna, Crucifixion and scenes from the lives of Peter and Paul (c.1300, Rome, central Italy)

5. The antependium with the crucifixion on a tree of life (late thirteenth century, north of the Alps)

6. Further reading

7. References

1. Introduction

Together with a large number of smaller fragments, the nine reworked liturgical textiles preserved in the treasury of Anagni Cathedral represent the material vestiges of the Cathedral’s exceedingly rich parament collection, which originated from donations made by Pope Boniface VIII (Benedetto Caetani, r.1294–1303). Caetani’s pontificate marked the climax of Christian universalism in the Middle Ages. In his Papal Bull Unam Sanctam (1302), Pope Boniface postulated the universal jurisdiction of the church in spiritual and secular matters. In addition he invoked the first Holy Year in 1300 and established the University of Rome, “La Sapienza”. He made systematic use of a wide variety of media for purposes of papal representation and facilitated, in particular, the development of innovative forms of depiction, in monumental sculpture in the form of half busts, statues and seated, enthroned figures.

Boniface VIII spent extensive periods of his pontificate in Anagni, which, along with Viterbo, Orvieto, Rieti and Perugia, was both an important thirteenth century papal residence outside Rome and Caetani’s home town. In 1303 he was held captive in Anagni for three days during an attempt on his life by Guillaume Nogaret, an envoy of his enemy King Philip the Fair of France, and Sciarra Colonna. He was liberated from captivity by the people of Anagni but died shortly after the incident in October of that year in Rome.

The fact that Boniface VIII made regular donations to the cathedral in his home town over the course of his frequent residences there is known from an inventory dating from around 1300 and preserved in the Archivio Capitolare in Anagni. It lists a total of 101 items, including 95 liturgical textiles and 12 liturgical vessels and objects made of metal and ivory, all of which originate from donations made by the Caetani pope at different times. Some of the textiles donated to the Cathedral by Boniface VIII were originally part of the papal treasury and were used in the context of the papal liturgy and court. The paraments preserved in Anagni were produced in various locations and can be assigned to different centres of weaving and embroidery in Europe and the Mediterranean region. Their heterogeneity reflects the diversity of the papal textile holdings around 1300, of which clear evidence is provided by the extant inventories of Papal treasures from the late thirteenth and early fourteenth centuries.

The appreciation, maintenance and occasional usage of these papal paraments in the Cathedral liturgy until well into the modern period is attested by a conservation measure recorded for the period between 1573 and 1576. The liturgical vestments were adapted to the period and for use in the Tridentine liturgy through the reworking of their cuts. Accordingly, as material witnesses of the papal donations made around 1300, they made an important contribution to maintaining the memory of Anagni’s heyday as a papal residence in the thirteenth century.

Apart from the aforementioned alterations undertaken in the late sixteenth century, the considerable discrepancy between the current state of some of the paraments and their original appearance can be explained by restoration work carried out in the 1960s.

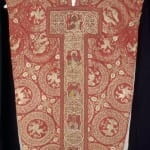

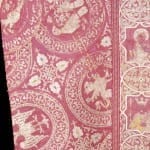

2. The paraments in opus cyprense (second quarter of the thirteenth century, possibly Cyprus or Sicily)

This group of four paraments, whose gold and silk embroidery imitates a fabric pattern and is executed on red samite, includes a cope, a chasuble and two dalmatics. The simulated pattern repeat consists of medallions featuring griffons, double eagles and paired parrots. The cope is the only piece to have more or less maintained its original state since the time of its donation by Boniface VIII. In their current form the two dalmatics and the chasuble go back to the reworking carried out from 1573. The material for the three newly produced paraments would have been provided by a cape, the form and design of which would have corresponded to the preserved cope, and at least one other parament.

Although the dating and location of origin of the gold embroidery is still disputed among scholars, it may at this point be assumed that it was produced in a western location. In addition to Sicily, favoured by many authors, Cyprus would also present itself as a suitable region, for the inventories of the papal treasury from around 1300 refer to the group of liturgical textiles that the Anagni donation is originating from as opus cyprense.

Regarding the original papal use of the paraments prior to their donation to Anagni, the cope was possibly a mantum, which along with the pallium, the tiara and white palfrey, formed part of the insignia of papal rule from the eleventh century at the latest. The immantatio, the enrobing of the Pope in the red mantum immediately after his election, was an expression of his investiture with papal authority. The mantum was traced back to the purple chlamys of the Byzantine Emperor and represented one of the material indications of the programmatic appropriation of the ruling insignia of the Roman empire by the papacy, as it formed part of the privileges promised to the pope by the Constitutum Constantini (Donation of Constantine decree exposed as a forgery in the fifteenth century). This is supported by the fact that the stylized animals featured in the medallions imitate the pattern repeats found in imperial Byzantine silks. Such animals were a common motif in the court attire of the imperial family and court officials in Constantinople in the mid-Byzantine period and were interpreted as symbols of the emperor’s power.

3. The paraments in opus anglicanum (late thirteenth century, England or France)

The inventories list both orphreys and entire paraments referred to as “English work” (opus anglicanum), which were usually embroidered with image cycles comprising multiple scenes. According to documentary sources, English embroidery was highly sought after in Curia circles and reached the papal court both through specially ordered imports and diplomatic gifts from the English royal household and English bishops. However, the high demand for opus anglicanum among Europe’s spiritual and lay elites of the period prompted the imitation of this originally English technique on the European mainland, hence the term opus angelicum should be interpreted as a trademark rather than a designation of origin in the strict sense. In the case of the Anagni Cathedral paraments it is therefore unclear whether they were produced in England or France.

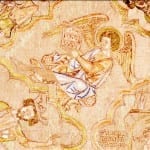

The opus anglicanum paraments in the Anagni collection – two copes and a chasuble – consist of a multi-layered linen ground, completely embroidered with gold and multi-coloured silk threads. The stitching is missing in some parts and the linen ground and parts of the underdrawing are visible.

The detailed pictorial narratives with multiple scenes comprising cycles of a Christological or hagiographic nature are characteristic of the group of paraments classified as opus anglicanum. The arrangement of the pictorial scenes, which are organised in a system of frames, is tailored to the legibility of the motifs while the garment is worn. Angels depicted within the system of frames, i.e. the spandrels between the medallions, function as a medium for addressing the viewer and define the reception parameters. These pointing or secondary figures mediate between the viewer and pictorial space with the help of lines of vision, gestures and presented objects.

The only piece that remains largely preserved in its original state is the cope with scenes from the life of the Virgin, and the childhood, Passion and Resurrection of Christ. In contrast, the chasuble with scenes from the life of St Nicholas is a product of the alterations carried out between 1573 and 1576 and was originally a dalmatic. The cope with the martyr saints was reworked secondarily in the course of the same measures, but its original state was reconstructed during the restoration work carried out from 1963 to 1965.

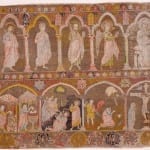

3.1 Cope with scenes from the life of the Virgin and the childhood and Passion of Christ

The cope presents a picture cycle comprising 30 scenes from the life of the Virgin and from the childhood, the Passion and the Resurrection of Christ. The central vertical axis, which is most clearly visible when the cope is worn, shows three scenes from the Marian cycle (Death of the Virgin, Assumption, Coronation). The angels swinging thuribles in the spandrels all face the Coronation scene in the centre and may be classified as accompanying figures.

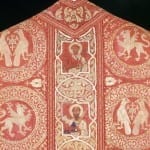

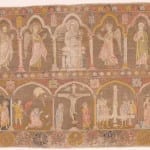

3.2 Cope with the martyr saints

The cope, which was reconstructed in 1963-65, is also decorated with a cycle comprising 30 scenes. The central vertical axis with a depiction of the Epiphany (adoration of the Christ Child by the Magi), the Crucifixion and the Holy Trinity is flanked by scenes from the martyrdom of apostles and saints. Hence Christ’s sacrifice on the Cross and its imitation in the martyrdom of the saints form the basic theme of the cope’s pictorial programme. Different groups of martyr saints, that is apostles, virgins, bishops, kings and knights, represent the totality of saints and stand for an imitatio Christi covering all periods, locations and classes.

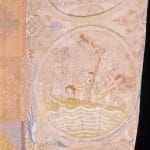

3.3 Chasuble (former dalmatic) with scenes from the life of St Nicholas

In its current form, the chasuble with the scenes from the life of St Nicholas is a product of the alterations carried out from 1573. This parament donated to Anagni Cathedral by Boniface VIII was a dalmatic with a cycle comprising at least 24 scenes from the life of the sainted bishop. St Nicholas was one of the most important sainted bishops of the Middle Ages and, following the transfer of his mortal remains to Bari in 1087, was particularly venerated in southern Italy and Rome. Apart from the standard representation in medieval art of St Nicholas as a performer of miracles (thaumaturgist), the representations shown on the former dalmatic highlight the saint’s episcopate and present him as a role model for spiritual office and the conduct of clerical life. The parament’s pictorial programme is possibly aimed directly at a cleric as the wearer of the vestment, presenting him with images depicting the exemplary fulfilment of his spiritual office.

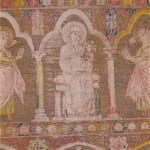

4. The antependium with enthroned Madonna, Crucifixion and scenes from the lives of Peter and Paul (c.1300, Rome, central Italy)

The context in which the antependium was commissioned is probably closely related, both spatially and temporally, to the creation of the former monumental fresco cycle with scenes from the history of the Apostles on the exterior wall of the porticus of Old St Peter’s which possibly dates to the end of Nicholas III’s pontificate (1277–1280), and the reworking of the fresco cycle on the same theme in the nave of St Paul Outside the Walls in the last quarter of the thirteenth century. The reception and adaption of selected scenes from these representative cycles from papal monumental art would also suggest that this textile object may have been the result of a papal commission, possibly issued by Boniface VIII himself.

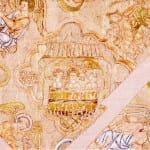

The antependium is divided into two registers. These are framed by linked medallions with pacing griffons and paired parrots. These appear to refer to the stylized animals of the paraments in opus cyprense, which were probably already held in the papal treasury when the antependium was commissioned. The upper register shows the enthroned Madonna with Child, flanked by the Princes of the Apostles Peter and Paul and other apostles. The lower register contains a depiction of Christ’s Crucifixion through three scenes from the lives of the apostles Peter and Paul.

The antependium’s pictorial programme is closely related to Rome. With the help of the textile medium, which transported the places in which the Princes of the Apostles were active and martyred to locations outside the urbs, virtual, new Romae arose, which rendered essential components of the understanding of papal rule, like the double apostolicity, visible.

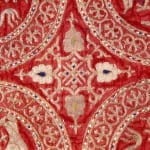

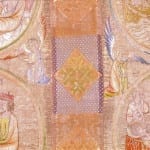

5. The antependium with the crucifixion on a tree of life (late thirteenth century, north of the Alps)

This antependium probably originated north of the Alps and can be dated to the end of the thirteenth century. The origin of the parament is difficult to determine as little embroidery has been conserved that is stylistically and technically comparable. According to the inventory of donations made by Boniface VIII to Anagni Cathedral, an altar cloth in ‘German work’ (opus theotonicum), executed in the white-on-white linen technique, was applied to the antependium. In any case, the iconography of the rugged cross (inserted into a tree of life), which is more or less absent from Italian embroidery, would certainly indicate that it was produced north of the Alps.

Because the embroidery has disappeared from large sections of the antependium, the foundation fabric (linen) is visible with the underdrawing. Interestingly, on closer examination it is possible to identify at least two underdrawings in black and red, which can probably be explained by changes to the design in the process of its emergence.

The antependium’s pictorial programme is Eucharistic in its orientation and should be seen as related to the altar as the place where the Eucharistic sacrifice of the Mass was performed. This can be concluded also by the fact that the altar was the location of use and bearer of the antependium. The pictorial field which is framed by 20 medallions is occupied by a representation of the Crucified Christ on a cross designed as a branch extending from a tree of life. This expresses the interpretation of the paradisiacal tree of life as the cross type, the lignum vitae as lignum crucis. A pelican, which is shown tearing its chest open to feed its young with its blood and can be interpreted (like the crucifix) in Eucharistic terms, is depicted on the branches growing out of the cross stem. The pictorial fields of the medallions feature enthroned, haloed figures (angels, kings, prophets, St Peter, crowned Madonna), almost all of which have extended index fingers pointing to the central event. The inscriptions distributed throughout the antependium, which originate mostly from the Old and New Testaments, are all Eucharistic in orientation and refer to interpretations of the redemptive event of the cross.

6. Further reading

– Christiane Elster, Liturgical Textiles as Papal Donations in Late Medieval Italy, in: Dressing the Part: Textiles as Propaganda in the Middle Ages, ed. by Kate Dimitrova ansMargaret Goehring, Turnhout 2014, pp. 65–79

– Christiane Elster, Päpstliche Textilgeschenke des späten 13. Jahrhunderts – Objekte, Akteure, Funktionen, in: Die Päpste und Rom zwischen Spätantike und Mittelalter. Formen päpstlicher Machtentfaltung, ed. by Norbert Zimmermann, Tanja Michalsky, Alfried Wieczorek, Stefan Weinfurter, scientific publication to accompany the exhibition „Die Päpste und die Einheit der lateinischen Welt. Antike – Mittelalter – Renaissance“ (Mannheim, Reiss-Engelhorn-Museen, 21.5.–31.10.2017)

– Christiane Elster, Die textilen Geschenke Papst Bonifaz’ VIII. an die Kathedrale von Anagni. Päpstliche Paramente des späten Mittelalters als Medien der Repräsentation, Gaben und Erinnerungsträger, Michael Imhof-Verlag, Petersberg 2018

7. References

- Conference “Textile Gifts in the Middle Ages – Objects, Actors, and Representations” (3.–5.11.2016) (PDF)

- Exhibition “Die Päpste und die Einheit der lateinischen Welt. Antike – Mittelalter – Renaissance” (Mannheim, Reiss-Engelhorn-Museen, 21.5.–31.10.2017)

- Alessandro Iazeolla’s series of photos in the online catalogue of the Bibliotheca Hertziana Photographic Collection

Photographs of the textiles: Alessandro Iazeolla (1989), www.alessandrojazeolla.it

Concept, texts and selection of images: Christiane Elster

Realization: Tatjana Bartsch, Charlotte Huber

Translations: Camilla Fiore (Italian), Baker&Harrison (English)

Digitization: Emiliano Di Carlo

1.4.2017