Memories of Rome. Drawings as Souvenirs around 1800

Content

EXHIBITION: December 12, 2024 to February 25, 2025

Bibliotheca Hertziana – Max Planck Institute for Art History

Palazzo Zuccari, Via Gregoriana, 28, 00187 Rome

Memories of Rome

The Bibliotheca Hertziana in Rome preserves in its graphic collection 97 drawings of views of the city of Rome and the Roman Campagna, which were bound in three albums when they were acquired at the beginning of the 20th century. A carefully executed and signed drawing with the portrait of the famous artist Felice Giani (1758–1823) on the first sheet suggests that he also drew the other drawings and that they are direct and atmospheric studies of nature and monuments. However, this is a marketing ploy, as almost all of the sheets are literal but more ephemeral copies of drawings by the Slovenian artist Franz Caucig (1755–1828), who was in Rome from around 1780–1787. Since Caucig, who later became director of the Academy of Fine Arts in Vienna, took all his drawings with him when he left the city, the Hertziana drawings must have been copied before his departure in 1787.

This online exhibition juxtaposes the copies with the originals. While the originals are carefully executed, the copies are more immediate and executed with less care, giving the impression of having been drawn quickly and directly on the spot, with hasty strokes and dark and contrasting washes. This certainly appealed to buyers who, in addition to purchasing carefully executed drawings and engravings, also wanted to acquire and own a testimony of the immediate travel experience.

While focusing on this group of drawings, the exhibition also presents another important work from the Hertziana collection that can be linked to the art market of the Grand Tour around 1800. The magnificent view of Rome, including the so-called Tempietto of the Palazzo Zuccari, was painted by the English artist John Newbolt (1803/05–1867), who also made several almost identical copies. These works are complemented by some contemporary and illustrated publications.

The online exhibition follows the structure of the on-site exhibition in the Sala Terrena of Palazzo Zuccari, adding information on the general theme and the individual exhibits.

"In Antiquities, the COLISAEUM Takes the Lead"

When writing about antique monuments in Rome in his “The Gentleman’s Guide in his Tour through Italy” Thomas Martyn states enthusiastically “In Antiquities the COLISAEUM takes the lead”. The book was published in 1787, at the same time as the Hertziana copies. It is therefore not surprising that the Colosseum plays a very prominent role in these copies as well as in the original drawings by Franz Caucig.

The appeal of the Colosseum was timeless. Yet its fascination seems to have increased during the Age of Romanticism, when the focus shifted from archaeological, religious and popular values to aesthetic and even ephemeral qualities.

Johann Wolfgang von Goethe described it, also in 1787, after returning from a nocturnal visit to the Colosseum: “It is impossible to imagine the beauty of a walk through Rome by moonlight without having experienced it. All individual objects are swallowed up by the great masses of light and shadow, and nothing but great and general outlines present themselves to the eye. For three days we enjoyed to the full the brightest and most glorious of nights. The Colosseum is peculiarly beautiful at such a time. It is always closed at night. A hermit dwells in a little shrine within its range, and beggars of all sorts huddle under its crumbling arches: the latter had lighted a fire in the arena, and a gentle wind carried the smoke down to the ground, so that the lower part of the ruins was quite hidden by it, while above the immense walls stood out before the eye in deeper darkness. As we paused at the gate to contemplate the scene through the iron bars, the moon shone brightly in the sky above. Meanwhile, the smoke found its way up the sides and through every crack and opening, while the moon illuminated it like a cloud. It was a most glorious sight.”

"Views in Rome"

Visitors to Rome were particularly fascinated by antiquity, especially the Colosseum, the Baths of Caracalla and Diocletian, the Pyramid of the Tomb of Caius Cestius and the temples of the Roman Forum. But also medieval buildings such as the Torre delle Milizie or the church of S. Agnese fuori le mura or the apse of the church of S. Giovanni e Paolo. In the course of the 18th century, the non-canonical views of the buildings became increasingly important. The engravings of Giovanni Battista Piranesi, which offered new views in terms of technique, archaeological criteria and representational conventions, were particularly popular with travellers. Piranesi’s first biographer, Giovanni Ludovico Bianconi, points out that Piranesi’s engravings made an impression on the “lontani” (which certainly also meant the Grand Tourists), while they did not always meet with the same interest among the locals, (‘perché chi era sul luogo non trovava sempre che questo interesse, questo calore corrispondessero al vero, benché piacesse infinitamente a noi pure una sì bella infedeltà. ‘) More and more views were added, intended to evoke both exclusivity and intimacy, and it is certainly no coincidence that the title of Pinelli’s work, published in 1834, is no longer ‘Views of Rome’ but ‘Views in Rome’.

"Vicolo di S. Isidoro di man manca"

The Vicolo di Sant’Isidoro leads directly to the Church and Convent of Sant’Isidoro, where in 1810 the cells abandoned by the monks became the residence of the community of painters known as the Brotherhood of Saint Luke, led by Friedrich Wilhelm Overbeck. The name of the adjacent Via degli Artisti suggests the colourful diversity of the artists who settled there. Franz Caucig lived in the Vicolo di Sant’Isidoro on the left (“di man manca”), sharing the house with “Giuseppe Bergler”, the painter Joseph Bergler (Salzburg 1753 – Prague 1829), with whom he was to have a lifelong friendship. During these years the painter Simone Pomardi (Monte Porzio 1757 – Rome 1830) also lived in the house, and from 1785 Michael Köck (Innsbruck 1760 – Rome 1825) and Felice Giani (San Sebastiano Curone 1758 – Rome 1823) joined the household.

"A mezzanotte dopo una cena pittorica in un Osteria"

There were many artistic communities in Rome, especially from the 18th century. They tended to group around the academies (such as the Villa Medici) and were often organized along regional lines. When Goethe came to Rome in 1786, he immediately went to live with the German painter Johann Wilhelm Heinrich Tischbein and remained in his German circle throughout his stay.

The Italian and polyglot artistic communities, on the other hand, reached not only a larger number of like-minded artists, but also a larger market for their works. They met to draw landscapes and monuments as well as nudes and sculptures, to discuss theory around the table or in the ‘Accademia dei Pensieri’ founded by Felice Giani in 1790, or simply to meet in larger groups to eat, drink and discuss. This is documented in a drawing by Felice Giani in the Moravska Gallery in Brno, inscribed “Disgnato da Felice Giani a mezanote doppo una cena pittorica in un Osteria all’arrivo di Michele Köck, a Roma, 1784”, which depicts the lively and probably rather alcoholic gathering of the artists.

Their main occupation was the copying of works, which served both to train and perfect their skills and to create an artistic reference library for the years after their stay in Italy. Hence the copying business flourished, especially the copying of oil paintings from famous originals. Some less solvent artists made a living from copying, and one can find complaints like that of the Hanau painter Friedrich Bury: “… I myself want to make an effort to get out of the copying business. … How I long to make a painting of my own, but circumstances do not yet allow me to do so.”

When the frigate Westmorland, sailing from Livorno to England, was captured by French ships in December 1778, it was found to contain 57 crates of various works of art bought in Italy by English tourists on the Grand Tour. In addition to original 18th century works and ancient sculptures, the crates contained many copies of works by important artists, notably after Raphael, Guido Reni and Domenichino. The boxes also contained a large number of engravings and prints, mainly by Piranesi, as well as drawings.

"Villa Negroni is a fine spot of ground..."

In 1787, Thomas Martyn, an English gentleman, also walked through the villas of Rome, both the historic ones and the modern ones, which he labelled with short and concise sentences such as: “Villa Negroni is a fine spot of ground…”

In the 18th century, the villa complexes increasingly attracted the attention of travellers to Rome. Visitors were particularly interested in the more modern buildings such as the Villa Albani. “Villa Albani is the only large villa complex built in Rome in the 18th century. In the second half of the 18th century it became synonymous with Rome, part of the myth of Rome”. The views by Caucig show the modern and elegant Rome, whose spacious villas are populated by elegant people.

"On leaving Rome … you will find many ancient sepulchres by the road side"

A visit to the Roman Campagna was an obligatory part of the itinerary. The nearby towns of Albano, Grottaferrata or Marino were visited on foot, on horseback, on a donkey or in a carriage. There were also regular excursions to Tivoli or Frascati, where people admired the aqueducts, viewed the panoramas, walked around Lake Albano and visited inns. Drawings of these places were in great demand, as were the engravings and etchings which tourists took with them to various countries.

The Appian Way was one of the main attractions. The many ancient tomb monuments fascinated learned travellers. In 1789, for example, the Englishman Sir Richard Colt Hoare wanted to follow in Horace’s footsteps and explore the entire length of the Via Appia from Rome to Brindisi. He paid the artist Carlo Labruzzi to accompany him as a draughtsman, a not uncommon practice as evidenced also by J.W.v. Goethe’s journey with the draughtsman Christoph Heinrich Kniep from Naples to Sicily (1787). Colt Hoare’s venture, however, had to be abandoned at Benevento, as he himself reports: “When I started from Rome, it was my decided intention to investigate the Via Appia along its whole extended line as far as Brundusium; but the advanced state of the season, the inclemency of the weather, and the ill health of my companion and artist Labruzzi, obliged me, very reluctantly, to abandon the further prosecution of my intended plan.” Labruzzis’ drawings are among the most important documents of the monuments of the Via Appia around 1800.

John Newbolt – View from the Pincio

Purchased by the Bibliotheca Hertziana on the Roman art market in 1976, this painting depicts a view of Rome from the Pincian Hill. The view, now obscured by modern buildings, shows St. Peter’s in the far background, with the Castel Sant’Angelo in front and St. Carlo al Corso prominently in the foreground on the right. The last landing of the Spanish Steps is marked on the right by the woman carrying a basket on her head. The left edge of the picture is defined by the light architecture of the portico designed by Filippo Juvarra, which was placed between the tall columns of the north side of Palazzo Zuccari in 1711, giving a Baroque focus to the square façade even before the Spanish Steps were built. On the small terrace are two young women, one holding a small child and the other holding a pink umbrella. At the entrance on the ground floor of Palazzo Zuccari, a street vendor offers the caretaker a basket of eggs, from which she appears to choose.

John Newbolt (also known as Newbott, 1803/05 – 1867) was an English painter from Wokingham who came to Rome in 1825 and lived there for the rest of his life. He earned his living mainly by painting scenes of Rome and the Campagna, which were mostly bought by English tourists. In the 3rd edition of Murray’s Travel Guide of 1853, he was described as “an English landscape painter of considerable merit, whose studio will enable the traveller to supply himself with admirable reminiscences of Roman scenery at very reasonable prices”.

The subject of Newbolt’s painting was apparently so successful that he himself copied it several times. One version is mentioned in the Kunstblatt of 16th of May 1837, thus predating our painting by three years. There are at least three versions with minimal changes. The egg seller was replaced by a monk, possibly to give the painting a more religious touch, as shown in a version of the painting (location unknown) used on the cover of a paperback book published in 1987[1] The same monk appears in another, smaller version of the subject, now in Antony House in Cornwall. [2] Newbolt’s practice of repeating a successful motif which combines the local view with bucolic romanticism and realism, at “reasonable prices” in his studio on a side street of the Via Sistina (Via Cappuccini) seems to have been applied to other Roman motifs as well – a practice still followed by contemporary painters of Roman scenes.

When the frigate Westmorland, sailing from Livorno to England, was captured by French ships in December 1778, it was found to contain 57 crates of various works of art bought in Italy by English tourists on the Grand Tour. In addition to original 18th century works and ancient sculptures, the crates contained many copies of works by important artists, notably after Raphael, Guido Reni and Domenichino. The boxes also contained a large number of engravings and prints, mainly by Piranesi, as well as drawings.

A book of reminiscenses

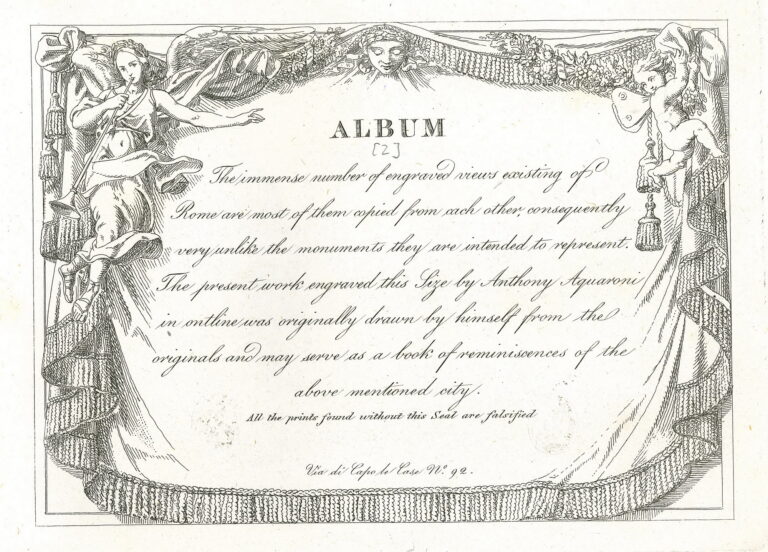

The title of this section is taken from the album of engravings of Roman monuments published by Antonio Aquaroni. In the preface, Aquaroni complains about the lack of originality and fidelity in the reproduction of the engraved works with views of Rome:

“The immense number of engraved views existing of Rome are most of them copied from each other; consequently very unlike the monuments they are intended to represent. The present work engraved this Size by Anthony Aquaroni in ontline (sic) was originally drawn by himself from the originals and may serve as a book of reminiscenses of the above mentioned city.”

Aquaroni’s complaint is certainly justified: as the drawings in the Hertziana also show, the copying business had developed a momentum of its own, moving further and further away from the works and finding its purpose primarily in the art market.

Aquaroni is pandering to tourists by promising them authenticity and truth, introducing himself as Anthony instead of Antonio, launching a seal of approval for the English market and pretending to be the one who, unlike his competitors, can tell it like it is. The goal was set: realistic rendering was desirable, romantic and imaginative representations in the style of Piranesi were out. Photographic reproductions from the 1850s onwards, which soon replaced drawings and engravings for tourists, had an easy time of it. Little did the world know that photography could lie even more than artistic reproduction…

All drawings from the series attributed to Michael Köck in the

collection of the Bibliotheca Hertziana can be consulted in the

Online Catalog of the Photographic Collection

The video of the on-site exhibition at Palazzo Zuccari

can also be viewed here:

Bibliography

- Black, Jeremy Black, Italy and the Grand Tour, New Haven u.a. 2003

- Coen, Paolo, Il mercato dei quadri a Roma nel diciottesimo secolo. La domanda, l’offerta e la circolazione delle opere in un grande centro artistico europeo, Florence 2010

- Culatti, Marcella, Villa Montalto Negroni. Fortuna iconografica di un luogo perduto di Roma, Venice 2009

- De Rosa, Pier Andrea, Pittori inglesi a Roma nell’Ottocento: John Newbolt, in: Strenna dei Romanisti 67 (2006), pp. 229–241

- Disegni di Tommaso Minardi (1787–1871), Galleria Nazionale D’Arte Moderna, Roma, (exh.cat. Rome), 2 vols., Rome 1982

- The Works of J. W. von Goethe, Letters from Italy, Vol. VI, translated by Alexander James William Morrison, London 1885

- Kieven, Elisabeth, Schlimme, Hermann, Palazzo Zuccari: Bau, Geschichte, Funktionen, in: 100 Jahre Bibliotheca Hertziana. Vol. 2: Der Palazzo Zuccari und die Institutsgebäude 1590–2013, Munich 2013, pp. 72–137

- Kieven, Elisabeth, “For the visual arts… the capital of the world, with which no other can be compared” Rome 1780–1787, in: Röll and Rozman 2018, pp. 11–14

- Martyn, Thomas, The gentleman’s guide in his tour through Italy. With a correct map and directions for traveling in that country, London 1787

- Murray, John, A Handbook for Travelers in Central Italy, Part II: Rome and its environs, 3rd ed. London 1853

- Olson, Roberta J.M. and Anna Ottani Cavina, Identifying Felice Giani’s Double Portrait with Michael Köck and the Friendship Portrait in Late Settecento Rome, in: Mitteilungen des Kunsthistorischen Institutes in Florenz, 55 (2013), 2, pp. 266–285

- Ottani Cavina, Anna, Felice Giani, 1758–1823, e la cultura di fine secolo, Milan 1999

- Röll, Johannes, Ein Porträt des Malers Franz Caucig in einem Zeichnungsalbum der Bibliotheca Hertziana, in: Römisches Jahrbuch der Bibliotheca Hertziana 40 (2011/2012), pp. 289–307; DOI: https://doi.org/10.11588/rjbh.2012.0.76974

- Röll, Johannes and Ksenija Rozman, Franz Caucig (1755–1828) Italienische Ansichten, Cyriacus. Studien zur Rezeption der Antike 11, Petersberg 2018

- Rozman, Ksenija and Ulrike Müller-Kaspar, Franz Caucig. Ein Wiener Künstler der Goethe-Zeit in Italien (exh.cat. Stendal), Ruhpolding 2004

- Rozman, Ksenija, Franc Kavčič/Caucig. 1755–1828, (exh.cat. Ljubljana), Ljubljana 1978

- Wegerhoff, Erik, Das Kolosseum bewundert, bewohnt, ramponiert, Berlin 2012

Imprint

Project and text Johannes Röll

Online Präsentation Tatjana Bartsch

Thanks for valuable help and support to Claudio Caucci, Alessio Ciannarella, Enrico Fontolan, Viktoria Guscinas, Susanne Kubersky, Celia Kieffer, Oliver Lenz, Pietro Liuzzo, Golo Maurer, Andrew McKenzie-McHarg, Ornella Rodengo, Marga Sanchez, Josephine Scheuer, René Schober, Christoph Stolz, Maria Tafelmeier, and Natalie Vitiello

Dedicated to the memory of Ksenija Rozman (1935–2024)

12 December 2024