Art and Architecture in Brazil

This special collection is one of the few online collections offering access to a broad and diverse panorama of cultural heritage in Brazil to support its study. Around 3.500 photographs taken by Tristan Weddigen on field trips to São Paulo, Rio de Janeiro, Salvador de Bahia, and Minas Gerais between 2005 and 2016 document art and architecture in Brazil since the early modern times. Neither systematic in their conception, nor representative of a photographic campaign, this special collection is rather a travel sketchbook following specific research interests.

The CIDOC-CRM ontology, developed by the Swiss Art Research Infrastructure (SARI) and applied in the EasyDB digital asset management system, makes the open-linked data findable, accessible, interoperable, and reusable (FAIR). Ana Paula dos Santos Salvat (São Paulo) has structured, defined, and linked the metadata of about over 900 objects following this technical state of the art.

Both photographs and metadata will be continually refined according to the latest technical standards. External contributions are welcome to expand the collection and improve the data.

A Historical Introduction

The city center of Salvador de Bahia, the capital of colonial Brazil from 1549 to 1763, named Pelourinho in direct reference to the “pillory”, recalls the history of the exploitation of enslaved Africans. The prosperity of this northeastern region of the former Portuguese colony is undeniably rooted in the success of the colonial sugar industry that was built on the backs of the enslaved population. The upturn in the colonial fortunes is mirrored in its ornate religious buildings, such as the Church and Convent of Saint Francis, which features gilded wood carvings and the Portuguese blue tiles, also referred to as azulejos after Flemish prints.

In the eighteenth century, gold, silver, and diamond mining became Brazil’s vital economic activity, as the name of its main region, Minas Gerais, attests. Its first regional capital was Mariana whose central square with a “pelourinho” is flanked by the baroque-colonial Churches of Saint Francis of Assisi and Our Lady of Carmo. The capital was then transferred to Ouro Preto, meaning “Black Gold”. In the Church of Our Lady of the Rosary, built in the late eighteenth century, the Brotherhood of Black Men would congregate.

The design ofthe curvy Church of Saint Francis of Assisi, among other buildings, is attributed to Antônio Francisco Lisboa, also referred to as “O Aleijadinho,” meaning “The Little Cripple”. Presumably of half-African descent, Aleijadinho, also a sculptor, created the Prophets and the Stations of the Cross of the Church of Bom Jesus de Matosinhos in Congonhas. By the beginning of the twentieth century, his spurious biography and unsecured oeuvre were amplified to make him a legendary Brazilian artist-hero after the model of Michelangelo.

In 1897, the regional capital was transferred to Belo Horizonte, Brazil’s first planned modern city. Later, its mayor, Juscelino Kubitschek, commissioned Oscar Niemeyer, Brazil’s state architect of sorts after Kubitschek was elected president, to create a leisure complex for the upper class around the artificial lake of Pampulha. Niemeyer’s Church of Saint Francis, inaugurated in 1943, regionalizes international, concrete, free-formed, machine-age modernism with references to the colonial-baroque architecture of Minas Gerais. That includes the wood cladding of the vault and the shallow chancel or the panels of blue tiles of the rear facade by Candido Portinari. A contemporary art park, the Instituto Inhotim, worthy of a rococo folly, was constructed near Belo Horizonte by a former mining businessman, Bernardo Paz, in 2006, whereby one pavilion was commissioned to Adriana Varejão, a specialist in the art of the aesthetic decolonization of Brazilian cultural heritage.

In view of the economic shift from sugar in the northeast to mining in the southeast, the national capital was transferred from Salvador de Bahia to Rio de Janeiro in 1763. Together with neighboring Niterói, the city of Rio de Janeiro holds the vestiges from the seventeenth to the nineteenth centuries, such as the “promenade architecturale” of Santa Cruz da Barra Fortress, the sober Monastery of Saint Benedict, the proto-modernist Carioca Aqueduct, and Parque Lage, with its tropicalized neo-medieval follies, which are local points of reference for modern buildings, such as Affonso Reidy’s Museum of Modern Art and Niemeyer’s many projects, including Museum of Contemporary Art in Niterói. However, Niemeyer’s Brazilian blend of White Modernism eclipses the social reality of poverty and racial segregation, as illustrated Favela, the etching by the Lithuanian emigré Lasar Segall.

However, it was Le Corbusier’s architectural style that heralded Rio’s modernist turning point, in particular his design for the Ministry of Education and Public Health building, which was largely modified and executed by Lúcio Costa, Niemeyer, Reidy, and others. While Le Corbusier himself tropicalized his five points of architecture, introducing features such as the movable brise-soleil, the Brazilians went a step further and regionalized his International Style with a wood cladding of the pilotis, Cândido Portinari’s azulejos, and Roberto Burle Marx’s tropical roof garden.

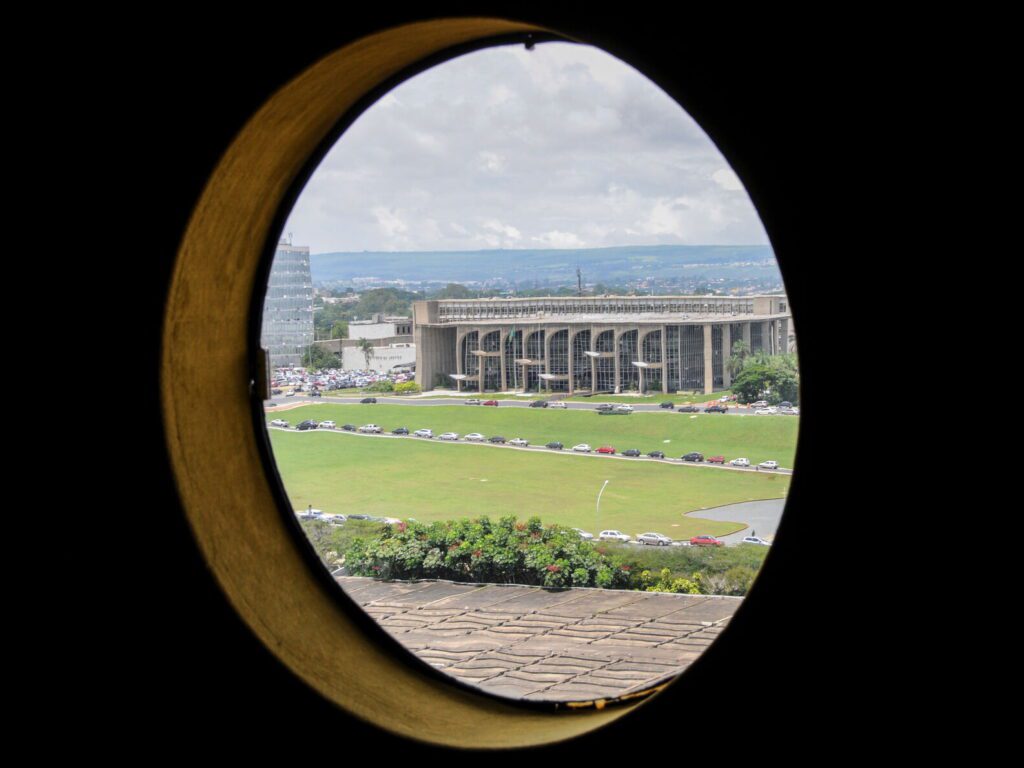

In 1960, Brazil’s capital was moved from Rio de Janeiro to Brasília, the newly developed capital city at the center of the country. Starting in 1956, Costa was responsible for the city’s master plan, while Niemeyer, among others, designed Brasilia’s iconic modernist buildings, such as the elemental National Congress Palace or the Palace of Justice with vertical brise-soleil. The integration of the visual arts was key to the construction of a national aesthetic identity. That included Athos Bulcão’s paneling facing the spiral staircase of the Itamaraty Palace, Marianne Peretti’s biomorphic stained glass, and Alfredo Ceschiatti’s neo-baroque, Aleijadinesque sculptures for the Church of Our Lady of Fatima, or Bruno Giorgi’s “Warriors” on the Plaza of the Three Powers, who came to be named “Candangos”, commemorating the migrant workers who built Brasilia.

From the end of the nineteenth century forward, coffee production in southeastern Brazil, especially in São Paulo, became an essential driver of development and industrialization, also making the region the country’s economic center. While initially enslaved people were brought in to work on the plantations, after the abolition of slavery in 1888, immigrants, predominantly Italians, were employed in plantation labor. However, Italians also became part of the growing urban capitalist elite that played a vital role in the development of Brazilian modernism, most prominently, the Matarazzo family. For instance, Francisco Matarazzo Júnior commissioned Marcello Piacentini to design his headquarters, in which a mosaic by Giulio Rosso celebrates the Matarazzo’s industrial power and connection to fascist Italy. Instead, Francisco Matarazzo Sobrinho founded the Museum of Modern Art of São Paulo in 1948 and the São Paulo Art Biennial in 1951, which now takes place in Niemeyer’s Ciccillo Matarazzo Pavilion at Ibirapuera Park. After World War II, Italian creators immigrated to Brazil. One is Lina Bo Bardi, who designed the Museum of Art of São Paulo (MASP) 1957–1968 – here represented by the self-taught painter Agostinho Batista de Freitas – and its revolutionary didactic display of paintings on glass slabs.

The modernism that was canonized with Tarsila do Amaral’s A Negra (1923), Oswald Andrade’s Manifesto Antropófago (1928), and Gregori Ilych Warchavchik’s own Casa Modernista (1927–1928) was integrated into the shifting constructions and mythologies of a national identity, from the post-war boom and military dictatorship to the recent social ascension and reactionary decline, has been questioned by contemporary artists espousing feminist, indigenist, political, and aesthetic points of view, such as in the works of Letícia Parente, Anna Bella Geiger, Maria Thereza Alves, or Marcelo Cidade.

Acknowledgements

We thank the following colleagues for their support:

- Jens Baumgarten, UNIFESP, São Paulo

- Emiliano Di Carlo, BHMPI, Rome

and the following institutions for the funding:

- The Getty Foundation, Los Angeles

- University of Zurich

Imprint

Text Ana Paula dos Santos Salvat und Tristan Weddigen

Photographs Tristan Weddigen

Data Ana Paula dos Santos Salvat

Online presentation Tatjana Bartsch

June 25, 2022