Giulio Romano – A Drawing from the Hertz Collection

Introduction

This research exhibition focuses on one of Giulio Romano’s preparatory drawings for the famous fresco cycle created for the great hall of Villa Lante on the Janiculum Hill, today preserved in Palazzo Zuccari. The recent restoration of the drawing, which represents The Liberation of Cloelia, has provided an opportunity to highlight the special appreciation for Italian Renaissance art, and especially for Giulio Romano, held by Henriette Hertz, the cosmopolitan collector and founder of the Bibliotheca Hertziana.

1. Henriette and Giulio

“An Albertinelli and a Giulio Romano, that seems like a good start.” In 1890, with much satisfaction, Henriette Hertz confided to her diary that she had acquired the first pieces of her art collection. Among them was Giulio Romano’s Madonna and Child – also called the Madonna Hertz – now housed in the Galleria Nazionale d’Arte Antica in Palazzo Barberini. Born in Cologne in 1846 and of Jewish origin, Hertz was at the time renting part of Palazzo Zuccari, where she resided with her childhood friend Frida Loewenthal and the chemist and collector Ludwig Mond.

Over the following decades, aided by the advice of dealers and art historians, including Jean Paul Richter and Ernst Steinmann, Hertz collected a considerable number of works, mostly from the Renaissance. Among the masterpieces in her collection was the famous fresco cycle with the Legend of the Janiculum Hill, produced by pupils of Giulio Romano for the Villa Lante. When Hertz finally acquired the entire Palazzo Zuccari in 1904, she had the cycle installed in its dining room.

Other rooms in her residence were decorated in the neo-Renaissance style by contemporary painters, including Edoardo Gioja, an exponent of the In Arte Libertas group. Gioja himself executed the portrait of Hertz exhibited here, purchased on the occasion of the present exhibition by the Bibliotheca Hertziana, which already possessed the preparatory drawing. To exalt her passion for the Italian Renaissance, Hertz had Gioja depict her in the pose of Renaissance portraits and dressed as a 16th-century noblewoman.

Through a series of drawings, prints and books from the Hertz bequest and related to Giulio Romano and the Villa Lante frescoes, the exhibition aims to highlight the late 19th-century collecting practices that Hertz cultivated: the acquisition, study, restoration, exhibition, photography, and publication of works of art.

Edoardo probably executed this preparatory drawing in the same year as the painting (1894). While the artist depicted the face and hands with great detail, he sketched the clothing and the landscape background only roughly. The drawing has been in the art collection of the Bibliotheca Hertziana since 1938. The then director, Leo Bruhns, acquired it for 350 lire from the artist’s heiress, Jenny Gioja.

The portrait depicts Henriette Hertz at the age of 48. The green velvet dress and lace blouse are inspired by 16th-century portraits by painters such as Titian, Palma il Vecchio and Lorenzo Lotto, and the technique — tempera on wood instead of the usual oil on canvas — is a deliberate reference to the early modern period. Edoardo Gioja, a pupil of Nino Costa and an Italian successor to the Pre-Raphaelites, had made a reputation as a portrait and landscape painter among the Roman bourgeoisie in the 1880s. Henriette had probably met him through her friend Lili Helbig, daughter of the well-known archaeologist Wolfgang Helbig, who took drawing lessons from Gioja.

The bronze statuette depicts Henriette Hertz working on a manuscript, perhaps her monograph on the early Renaissance painter Pinturicchio.

The statuette was made by the sculptor Ferdinand Seeboeck in 1890, on the occasion of the birthday of Ludwig Mond, his patron and sponsor. Mond very often financially supported the young artists to whom Hertz also entrusted important commissions. One such artist is Edoardo Gioja, who portrayed Mond in the decoration of the salon of Palazzo Zuccari.

Over the years, all the rooms of Palazzo Zuccari were filled with the collection items acquired by Henriette Hertz, including numerous works from the Italian Renaissance, as can be seen in the historical photographs of Hertz’s apartment and the studios of the newly founded institute.

2. Acquisition

In 1892, thanks to the mediation of Jean Paul Richter, Henriette Hertz acquired the cycle of frescoes with Scenes from the legend of the Janiculum Hill. The cycle, which was attributed at the time to Giulio Romano, had adorned the Salone of Villa Lante for three centuries. Today the authorship of the frescoes is usually attributed to Giulio Romano’s pupils Polidoro da Caravaggio and Maturino da Firenze. Originally built for Baldassarre Turrini, the villa became the property of the Lante family in 1551 (hence its name) and was acquired by the Borghese family in 1817. They removed the frescoes twenty years later, after the building was taken over by the religious community of the Sacro Cuore. In 1892, the removed frescoes were auctioned off along with other collection items from the Borghese estate. An original copy of the Borghese catalog was acquired for the holdings of the Bibliotheca Hertziana on the occasion of this exhibition.

3. Display

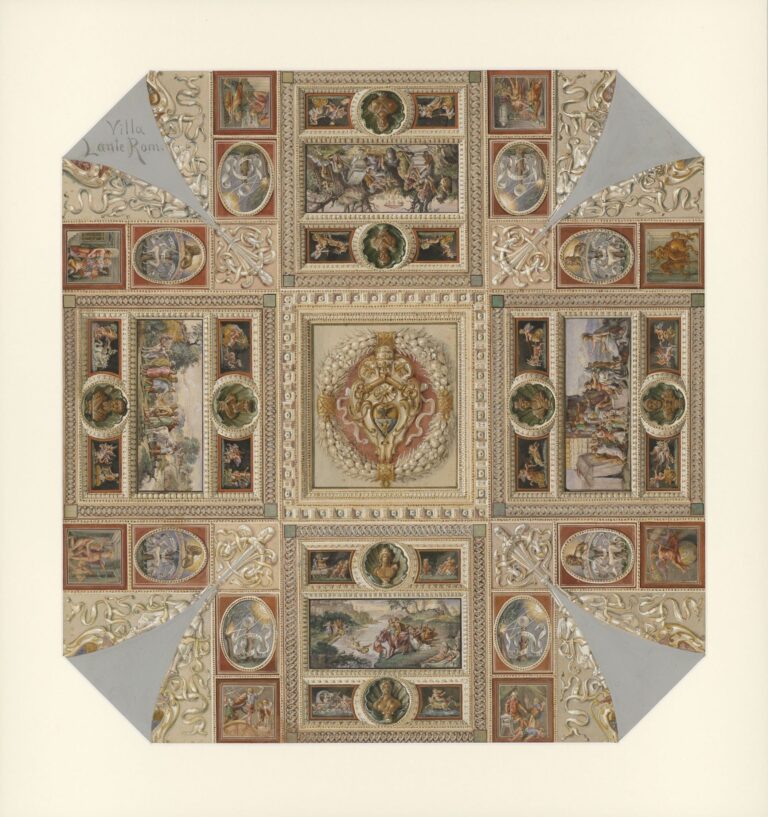

To accommodate the frescoes in their new location, Henriette Hertz commissioned painter and decorator Alessandro Palombi to complete the decoration of the dining room ceiling between 1904 and 1905. The paintings were placed in a wooden ceiling that imitated the original stucco ceiling and was interspersed with neo-Renaissance-style grotesque decorations and chandeliers to fill the spaces originally occupied by stucco busts.

In the center of the vault, to replace the Borghese coat of arms that remained at Villa Lante, Palombi painted an oval depicting the Capitoline she-wolf with the twins Romulus and Remus. The preparatory drawing for this part of the fresco has also been preserved. Until 1917, the drawing must have belonged to Mariano Cannizzaro, the architect of the Hertz household, who then offered it as a gift, complete with a dedication, to the painter Alide Gollancz, Henriette Hertz’s niece. Visible in the left foreground is the ficus ruminalis, the legendary wild fig tree that grew on the banks of the Tiber when the twins were found. In the background we see the main monuments of Rome, which symbolically represented the three most prosperous phases of its history. On the right, the Temple of Jupiter Capitolinus serves as an emblem of the power of Ancient Rome. On the left, the Piazza del Campidoglio alludes to the power of Renaissance Rome, while in the center the Monument to Victor Emmanuel II, still under construction when the design was executed, is clearly legible, referring to Rome as the capital of the newly united Italy.

In the final work, the Temple of Jupiter was replaced by a fortress representing the mythical founding of the city on the Palatine Hill. The changes carried out over the course of the work’s development were perhaps due to Henriette’s choice to emphasize the political supremacy of ancient Rome, rather than its religious supremacy. In any case, the depiction is emblematic of Hertz’s desire to glorify the city of Rome as Europe’s most prolific political and cultural center, rooted in antiquity. Henriette described Rome this way in her diary: “an eternal poem, to which each century adds a new verse.”

4. Documentation

Henriette Hertz purchased the frescoes with scenes from the History of the Janiculum Hill, at the time attributed to Giulio Romano, on March 30, 1892 for 20,000 liras from the Borghese family. Between 1905 and 1907 Jean Paul Richter studied them in order to publish them in 1928 in his book on the Hertz Collection, together with this watercolor, most likely painted by Moritz Meurer. The watercolor faithfully reproduces the ceiling of Villa Lante’s great hall, with its fresco and stucco decoration.

5. Restoration

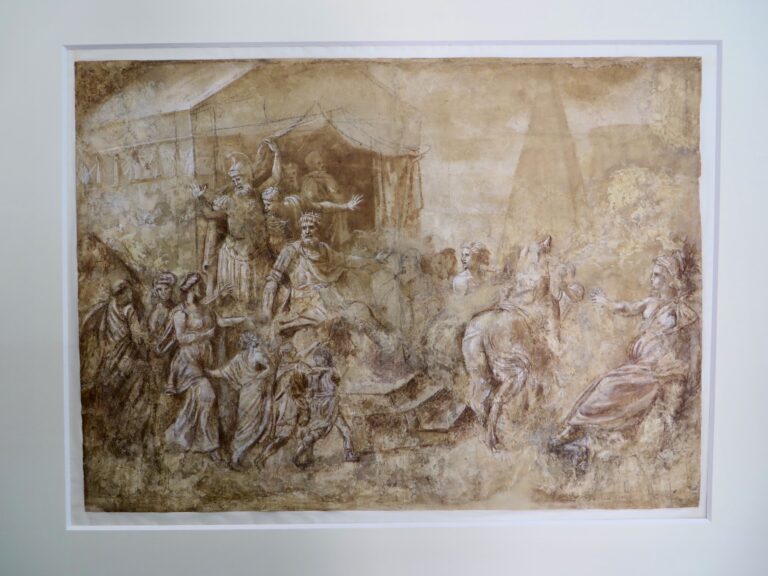

Giulio Romano, The Release of Cloelia, c. 1524, watercolor and brown ink on paper, 39.8 x 54.8 cm, after the restoration, Rome, Bibliotheca Hertziana

Among the most important pieces of the Hertz collection still preserved in Palazzo Zuccari is the drawing by Giulio Romano, The Liberation of Cloelia. It depicts an episode from the history of the war between the Etruscans and Romans at the end of the sixth century BC, the liberation of the Roman heroine Cloelia, who had been taken hostage by the Etruscan king Lars Porsenna. This is a preparatory drawing for a scene from the fresco cycle that Giulio Romano’s pupils, Polidoro da Caravaggio and Maturino da Firenze, painted on the vault of the great hall of Villa Lante on the Janiculum Hill around 1525. The attribution of the folio to Giulio Romano dates back to the late 19th century and has been confirmed by more recent studies as well.

The drawing’s precarious state of preservation was worsened by a poor restoration in the late nineteenth or early twentieth century. It is not known whether these measures were commissioned by Henriette Hertz, but it was in keeping with the spirit of the time to make a severely damaged work such as this legible again through heavy overpainting, additions, and corrections, without regard for its original condition.

A consolidation of the drawing carried out on the occasion of the exhibition and accompanying technological examinations have confirmed the high artistic quality of the better preserved parts in the upper half of the folio. X-rays revealed a number of pentimenti; for example, the face of King Porsenna was originally turned in the opposite direction, towards the waiting horse.

The sheet must have already been in precarious conditions when Henriette Hertz purchased it, since it shows strong traces of late 19th or early 20th century restoration work. It is not known whether this intervention was commissioned by Henriette Hertz, but in any case it testifies to the restoration methods common at the time, in which severely damaged works such as this were made ‘legible’ again by overpainting, additions, and corrections without regard for the original.

The sheet must have already been in precarious conditions when Henriette Hertz purchased it, since it shows strong traces of late 19th or early 20th century restoration work. It is not known whether this intervention was commissioned by Henriette Hertz, but in any case it testifies to the restoration methods common at the time, in which severely damaged works such as this one were made “legible” again by overpainting, additions, and corrections without regard to the original.

The Drawing before Restoration

The Restoration of the Release of Cloelia

After restoration

A consolidation of the drawing carried out on the occasion of the exhibition and accompanying technological examinations have confirmed the high artistic quality of the better-preserved parts in the upper half of the folio. X-rays revealed a number of pentimenti.

Under the surface

This infrared image shows several interesting changes of design (pentimenti) that the artist made during the artistic process. Evidently, the Etruscan king Porsenna was initially intended to turn his head to the left towards the figure that is about to mount the horse, who can be identified as Cloelia. In the final drawing, however, the king turns his head to the right, where Cloelia is approaching, surrounded by her companions. The female hero is thus represented twice in this scene.

A Two-headed King

In the infrared image, it looks as if the king has two faces. By favoring the right turn of the head, Giulio Romano decides to assign more weight to the tense moment just before the king acquits Cloelia. The scene with the horse in the right part of the picture anticipates the story’s happy ending.

Original or Later Addition?

The poor condition of the drawing led to its misfortune in critical literature. After the sheet had apparently been folded in two in the middle and exposed to moisture, the separation of the two halves of the sheet that were stuck together caused remarkable losses, especially in the lower part of the sheet. Attempts were made to repair this damage in the 19th century by crude restoration interventions, but these further damaged the drawing, as can be easily seen in this synchrolight scan. Only the reasonably well-preserved upper part, marked here with a red border, allows conclusions to be drawn about the original condition of the sheet.

6. Study

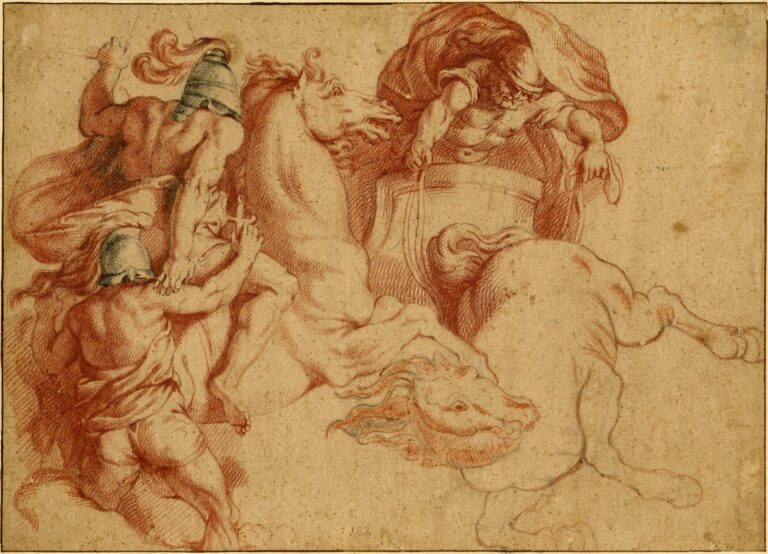

Around 1900, stylistic analysis became the most popular method of study among art historians. Among Henriette Hertz’s advisors was art historian Jean Paul Richter, a student of Giovanni Morelli, who advocated this approach. At Richter’s suggestion Hertz purchased some folios for her collection of prints and drawings, including the Battle Scene with Roman Soldiers and Horses and David and Goliath, both closely related to Giulio Romano’s inventions.

The Battle, executed in red and black chalk, was sold at auction in 1839 as an autograph drawing by Giulio and entered the Hertz collection at an unspecified time. The folio bears the mark of Danish collector Johan Conrad Spengler, who may be responsible for the gilt framing and mounting on blue cardboard, to which the attribution “Giulio Romano” was added. It is more likely that the drawing is an eighteenth-century academic copy from a late sixteenth- or early seventeenth-century model close to an invention of Giulio’s, but not attributable to him with certainty. Even in the inventory of the Hertz collection compiled in 1913, the Battle appears as a “facsimile” of a drawing by Giulio. Evidently the study of the work led Henriette Hertz and her advisors to change the attribution from the master to his followers or imitators.

In addition to the acquisition of artworks, the collecting practice of the early 20th century often included the gathering of various materials on a particular artist, which were intended to scientifically complement the actual collection pieces. This also happened in the case of Giulio Romano in the Hertz Collection. After significant works such as the Madonna Hertz and the Villa Lante frescoes had entered the collection, prints, photographs, reproductions, and other material regarding Giulio Romano were acquired.

The portraits of Giulio Romano shown here are examples of the heterogeneous materials that could be included in such a study collection. Their acquisition most likely goes back to the founding director of the Hertziana Ernst Steinmann, who was an expert on 16th-century prints. Besides his publications, Steinmann’s most important scientific legacy is his large collection of drawings, prints, casts, statues and books on the work of Michelangelo.

7. Collecting

In addition to the acquisition of artworks, the collecting practice of the early 20th century often included the gathering of various materials on a particular artist, which were intended to scientifically complement the actual collection pieces. This also happened in the case of Giulio Romano in the Hertz Collection. After significant works such as the Madonna Hertz and the Villa Lante frescoes had entered the collection, prints, photographs, reproductions, etc. regarding Giulio Romano were acquired.

The portraits of Giulio Romano shown here are examples of the heterogeneous materials that could be included in such a study collection. Their acquisition most likely goes back to the founding director of the Hertziana Ernst Steinmann, who was an expert on 16th century prints. Besides his publications, Steinmann’s most important scientific legacy is his large collection of drawings, prints, casts, statues and books on the work of Michelangelo.

8. Photography

Since the 1880s Henriette Hertz and her colleagues had enthusiastically used photographs not only to document and study works of art, but also as material for independent display. Henriette’s acquisition of the fresco cycle from the Villa Lante is documented in the 1892 auction catalog. An original copy of the Borghese sale catalog entered the collection of the Bibliotheca Hertziana on the occasion of this exhibition.

Following the purchase of the frescoes, the photography house founded in Rome by photographer James Anderson photographed the detached paintings, cataloging them in 1899 as the “Harry Hertz Collection.”

9. Publication

It was Henriette’s lifelong friend Frida Mond who, after Hertz’s death in 1913, proposed that a catalog be published on the Hertz Collection and Giulio Romano’s frescoes at Palazzo Zuccari. The efforts that went into the book are documented in a correspondence between Jean Paul Richter, author of the catalog, Ernst Steinmann, founding director of the Hertziana and editor of the publication, and Robert Mond, who funded the project and wrote its preface.

The book was released in 1928 in Leipzig with a print run of 300 copies. The title page was designed by the well-known illustrator Marcus Behmer and accompanied by a photograph of Henriette Hertz’s bronze bust, cast by the sculptor Adolf von Hildebrand in 1911.

From this correspondence, some disagreements about the photographic kit emerge. According to Robert Mond, the photographs should have been in color, whereas, according to Steinmann, high-quality black-and-white images were needed to better demonstrate the scientific value of the book.

The importance Steinmann attributed to the Villa Lante frescoes (which were, at that time, still believed to be authored by Giulio Romano himself) is made clear by a letter sent to Richter in November 1927, in which he proposes to title the volume Gli affreschi di Giulio Romano e la collezione Hertz nel Palazzo Zuccari. In Steinmann’s view, the paintings deserved to be recognized by a wide audience.

Selected Bibliography

100 Jahre Bibliotheca Hertziana – Max-Planck-Institut für Kunstgeschichte. Der Palazzo Zuccari und die Institutsgebäude 1590–2013, ed. by Elisabeth Kieven, Munich 2013.

100 Jahre Bibliotheca Hertziana – Max-Planck-Institut für Kunstgeschichte. Die Geschichte des Instituts 1913–2013, ed. by Sybille Ebert-Schifferer, Munich 2013.

La donazione di Enrichetta Hertz, 1913–2013, ed. by Sybille Ebert-Schifferer e Anna Lo Bianco in collaboration with Cecilia Mazzetti di Pietralata and Michela Ulivi, Cinisello Balsamo 2013.

Christoph Luitpold Frommel, „Giulio Romano e la progettazione di Villa Lante“, in Ianiculum – Gianicolo, ed. by Eva Margareta Steinby, Rome 1996, pp. 119–140.

Jean Paul Richter, La collezione Hertz e gli affreschi di Giulio Romano nel Palazzo Zuccari, Lipsia 1928.

Julia Laura Rischbieter, Henriette Hertz, Mäzenin und Gründerin der Bibliotheca Hertziana in Rom, Stuttgart 2004.

Villa Lante al Gainicolo. Storia della Fabbrica e cronaca delgi abitatori, ed. by Tancredi Carunchio e Simo Örmä, Rome 2005.

Imprint

Project Susanne Kubersky-Piredda, Gaia Mazzacane, Oliver Lenz

Photography Enrico Fontolan

Texts Susanne Kubersky-Piredda, Gaia Mazzacane

Translations Marina Hopkins (ing), John Rattray (ing), Julia Hagge (ted)

Realisation Ksenia Yurina

Restoration Lorena Tireni, (Aurea Charta), Serena Galetti, Emiliano Africano, Lorenzo Civiero

Technological examination Claudio Seccaroni, Giuseppe Marghella (ENEA, Roma)