Focus on Amatrice

Earthquakes and photography—recording the past, planning the future

An online exhibition by Francesco Gangemi, Rossana Torlontano and Valentina Valerio in collaboration with the Photographic Collection

Introduction

A seismic region

As it was

Photographs of the catastrophe

Amatrice in black and white

What remains

What future?

To learn more

The research group

Introduction

Why a digital exhibition? The earthquake of 2016 and the subsequent seismic sequence have dramatically changed the face of Amatrice: lives were lost, the urban fabric was disrupted, and endangered monuments were destroyed. Today, Amatrice looks deserted: two towers stand isolated, the last trace of the medieval structure, the symbol of a vanished city now reduced to piles of rubble.

How to describe the variety and richness of the cultural legacy that was lost? And how to convey the gravity and extent of the damage through images, without succumbing to the aesthetics of catastrophe? This digital exhibition is designed to offer an opportunity to reconnect the surviving artworks and monuments to their lacerated contexts, to question the fate of the debris—without lingering over the pathos—and to restore the temporal dimension of the earthquake, its long duration.

Objectives. This exhibition starts from the recognition of earthquakes as recurring natural events in a seismic territory such as Amatrice, and from the awareness that the fate of damaged cultural heritage depends on choices made initially in an emergency. With its historical center ravaged by the earthquake and—by now—erased nearly completely by the removal of rubble, Amatrice’s memory is entrusted to photography. But that’s not all: the images also serve as a starting point for future measures of preservation and reconstruction; they are an instrument for documentation and knowledge. This exhibition aims to collect and organize historical photographs in juxtaposition with images made directly after the earthquake and during the periodic monitoring campaigns done by the Bibliotheca Hertziana. Given the current impossibility of reconstructing the face of Amatrice, the photographs collected on this website replace (at least virtually) the lost cultural unity of the area, and invite us to reflect on the forms, methods, and purpose of the reconstruction that will have to be done.

A seismic region

Amatrice sits on a plateau at the heart of a historically seismic region and is surrounded by the peaks known as the Monti della Laga and the Monti Sibillini. This is at the core of the Apennine range, a mountain chain that owes its rugged profile to recurrent telluric shifts. The uneven and imposing morphology of the landscape surrounding the urban center, the mountains marked by deep cracks and fractures, bear witness to the age-old instability of this region that is hit cyclically by strong earthquakes. Particularly destructive quakes struck in 1639 and 1703; the first one was detailed in a chronicle from the same year written by Carlo Tiberi (Nuova e vera relatione del terribile e spaventoso Terremoto successo nella città della Matrice e suo Stato con patimento ancora di Accumulo e luoghi circonvicini). “The earthquake,” he writes, “tore down and destroyed houses and palaces, so that the remains of Amatrice are only barely visible.”

The seismic sequence that started on the night of August 24th, 2016, and continued with other strong tremors in October 2016 and January 2017, was a watershed in Amatrice’s history. The effect of this violent seismic swarm on the intrinsically fragile foundation of buildings was devastating: it caused 299 casualties, and the damage was soon ranked as one of Italy’s worst disasters of the century. Aerial photographs demonstrate the progressive destruction of the town as collapses worsened after the earthquake of October 30, 2016. This is evident from panoramic views taken in November 2016, showing an urban landscape that is still recognizable but completely destroyed.

After the catastrophe, the urban center deteriorated into a changeable reality in which the succession of tremors, emergency measures, and rescue and rubble-removal operations continually altered the look of the city. In Amatrice, the heart of public life had been the Corso Umberto I, a street that divided the town in two, and its tower, the Torre Civica, standing tall as a symbol of the community. This photographic series (below) illustrates the phases of the town’s main artery in the months following the disaster: rubble fell atop older rubble, blocking all access; later, the roadway was restored, and lastly, the remains of the urban backdrop reappeared after the final debris was removed. These images condense two years of Amatrice’s history, and they document—as the rubble is being heaped together and carted away from the shade of the tower—the metaphysical condition into which the Corso fell. The street where once you strolled at leisure, the street embedded in the everyday setting of shops, bars, and offices, is now closed, with fences marking the red zone, and you drive along it quickly, and only in a motorized vehicle. The photography documents the history of the disaster.

As it was

The urban form: project and context. “From the very beginning, [the town] must have been built with a lot of symmetry, with good streets, and public squares for the citizens’ convenience, and a fountain in one of them.” The erudite Neapolitan Lorenzo Giustiniani described Amatrice this way at the end of the 18th century, identifying the geometry of the rectangular street grid as the ordering element of the town’s design. This regularity in the layout is the result of a planning rationale similar to that of other centers that were newly founded at the beginning of the Angevin era (when the French Anjou dynasty reigned over part of the Italian peninsula): like Leonessa, Cittareale, Cittaducale, and other villages, Amatrice was shaped when mountain folk were sent to live in a new colony inspired by the French bastides, the towns erected in the Midi during the conflict between the French crown and the English crown. This very urban design, while not documented by historical sources, is what integrated Amatrice into the reorganization of the population and the institutional reorganization of the mountain area on the border between the Kingdom of Sicily and the Papal States, a strategically important region. Indeed, the magistrate responsible for the jurisdiction and the surveillance of the borders of the Anjou realm (known as the Capitano delle Terre di Montagna) lived in Amatrice from the start of the reign of the Angevin Charles I (1266–1282).

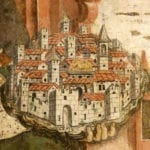

Aerial views highlight the town’s cruciform road system, marked at the chief intersection by a tower; this Torre Civica (documented since 1293) stands by the town hall—a central positioning that was to testify to Amatrice’s status under the direct control of the crown. Like the other two towers that survived until the recent earthquakes—the bell towers of the churches of Sant’Emidio and Sant’Agostino—this one is characterized by rusticated blocks of sandstone masonry on the walls, and cusps at the top. The three structures combined the bell-tower function with their function as urban towers, elements of the defensive system; this is evident in the case of Sant’Agostino, where the bell tower sat directly against the town entry gate called Porta Carbonara, which means “near the moat.” Antique views show a crown of towers surrounding what the traveler Edward Lear, in the mid-19th century, called “the deserted walls of Amatrice”; walls that—according to the 16th-century Life of Camillo Orsini by Giuseppe Orologi—had six gates, none of which remain today.

Monumental legacy. On the eastern and southern edges of the town were the convents of the Augustinians and the Franciscans, respectively—Amatrice’s two major religious complexes. Each domus followed the mendicant tradition of occupying a spot on the edge of the city, marking a new direction for urban expansion and eventually incorporating part of the city walls into its complex. This relative marginality actually favored the friars’ control over some access gates, with clear commercial purposes. This is evident in the case of the Franciscan settlement, which is documented back to the final quarter of the 13th century, and which soon took on the role of religious epicenter for the town. It is no coincidence that a belt of churches and oratories grew up around the complex of these Friars Minor: it became a religious district reflecting the Order’s power as an economic linchpin in a territory firmly controlled by the crown.

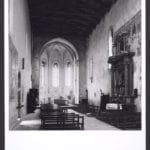

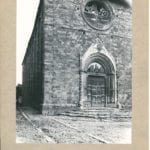

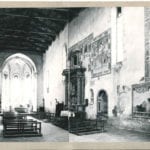

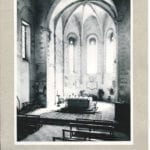

Moreover, the Franciscans’ leadership role in Amatrice was already established by the relationship of their convent to the urban space: the convent buildings were clearly outsized in the context of the town. The convent’s out-of-scale proportions show up again in the size of the church of San Francesco, a structure with one nave and a polygonal apse. Both the shape of the choir and the handling of the sides (with pilaster strips) are common elements in central Italian mendicant architecture, but Amatrician churches have a particular feature that might be ancient kind of earthquake-proofing: a band of low arches sitting on corbels.

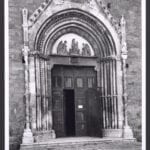

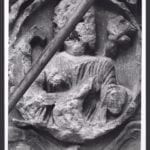

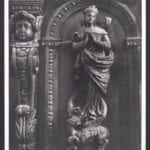

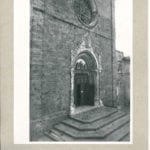

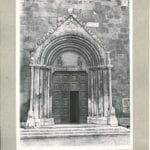

On the façade of San Francesco is the main external decoration: a pointed portal that was obviously inspired by the main portal of the Minorite church in the town of Ascoli Piceno (which was, not by chance, the seat of the diocese that embraced Amatrice). The design follows a typology that was widespread in Abruzzo in the 14th and 15th centuries and is adorned with crockets (curling leaves) climbing the pointed gable, and with slim columns that have shaft rings and chevrons. These are all elements of the mature Gothic lexicon, but here the lexicon is shorn of decorative exuberance: the general sobriety is typical of the Apennine culture of Umbria and Lazio. The decoration of the lunette—which miraculously survived the earthquake—is extremely interesting in itself: it is a polychrome sculptural group in stone with the Madonna and Child enthroned between two angels and surrounded by angelic figures painted in the underside of the arch, and it corresponds iconographically and formally to the similar composition in the lunette portal of the church of San Benedetto in the town of Norcia.

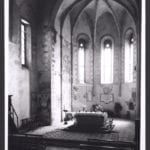

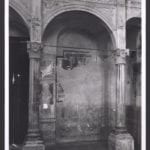

This indicates a fluid network of artistic relations, typical of the Mid-Apennine frontier, in which—as we will see in the fresco decoration—the influence from Ascoli Piceno often dominates, probably thanks to the Franciscans. The leading role played by this Order in Amatrice is evident also in the Augustinian church, which contrasts with the layout of the Minorite model: this building has a single nave, closed by a rectilinear choir; again, its façade is horizontal and its flank is girdled with lowered arches on pilaster strips. The portal of Sant’Agostino, dated 1428, in accordance with the emulative character of the building to which it belongs, also represents an evolution: the original Gothic work is developing proto-Renaissance forms.

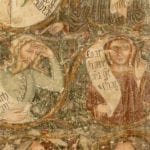

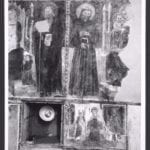

The figurative evidence. In the urban churches, the earliest figurative evidence dates to the turn of the 14th century into the 15th, at the time of the city’s greatest wealth, which was marked by the link with the artistic culture of Ascoli Piceno that penetrated the Amatrician valley along the Apennine road network. The great mendicant church of San Francesco housed the most important traces of this artistic event, expressed in the rich decorative cycle of the wall frescoes (severely damaged by the earthquake). The precious frames around many of the fresco scenes gave a sense of unity to the decorative program, which was actually the work of several painters organized in associated workshops according to a practice that was wide-spread along the Apennine ridge, and which surely encouraged the circulation of styles and models. At least four workshops can be distinguished inside San Francesco, and their work—stretching across almost a full century—demonstrates the artists’ attempts to interpret new developments in the painting of Umbria and Le Marche.

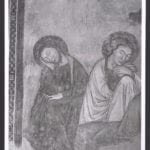

Among the first scenes is the depiction of Tree of Jesse on the apse, created in the late 1300s by a painter close to the school of Allegretto Nuzi. Subsequently, the workshop responsible for the majority of the decorations took over; among its strongest works is the beautiful Nativity on the north wall, which was damaged but fortunately not destroyed by the earthquake. The same workshop—which also worked in the crypt of Santa Maria in Platea in the town of Campli (Abruzzo)—was responsible for the frescoes on the south wall: the Last Judgment, which grew patchy and became hidden in the 17th century by the remarkable polychrome wooden altar, and also the series of the Death of the Virgin and the Coronation of the Virgin, now lost because of the collapse of the entire flank of the building.

The numerous other 15th-century frescoes in San Francesco (the notable Tree of Jesse on the southern wall and the equally remarkable Enthroned Madonna with a representation of Amatrice on the counter-façade) reveal the changes in the cultural framework that occurred in Le Marche. The final painters working in the church assimilated—in their own cursive and vernacular version—the international cadences of the Salimbeni brothers as well as the refined stylistic elements of Gentile da Fabriano and the innovations introduced by the arrival of Venetian paintings in Ancona and Camerino.

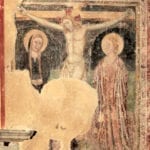

The complex decorative program of San Francesco left a strong imprint on the local figurative culture, starting from the frescoes of the ancient church of Sant’Emidio, which became the home of the local museum, “Cola Filotesio.” In it, the same courtly cadences return, updated with the Salimbenis’ more modern notes, as in the monumental Crucifixion. The reference to the pictorial civilization of Le Marche continues outside the town of Amatrice in the sanctuary of Santa Maria della Filetta, built in one of the many country villas, where in the 1470s the Crivelli-esque painter Pierpalma da Fermo signed the glowing frescoes in the apse: this was a high point of Amatrician artistic production. The paintings are linked to the precious reliquary made for the same sanctuary by the famous goldsmith Pietro Vannini from Ascoli Piceno.

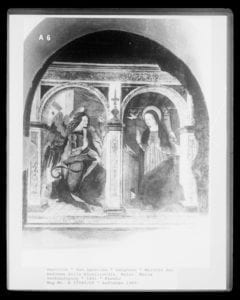

In this context, a new artistic personality emerges, seemingly inspired by the Madonna of Mercy painted on the right wall in the sanctuary of the Passatora Icon near the village of Ferrazza. Also attributed to this same artist, whose stylistic development has been reconstructed recently, is the important niche frescoed with an Annunciation (dated to 1491) on the left wall of Sant’Agostino in Amatrice. This anonymous master must have been the head of a workshop active in the territory for about thirty years, which reached its most complete expression in the painting program of the sanctuary of the Passatora Icon. This workshop likely trained both Dionisio Cappelli—who left several signed works in Amatrice and Arquata del Tronto—and the young Nicola Filotesio.

Nicola Filotesio, known as Cola dell’Amatrice, changed the course of this story; he was the city’s most important artist, although his only work remaining there was his 1527 Holy Family. Cola’s success in Rome shifted the interest of Amatrician artists towards the great city. Amatrice thus became part of the “periphery” of Rome and the northern edge of the Sabine Hills, at the end of the 15th century, after having been a bulwark on the Apennines of an original and composite figurative tradition dominated by some stylistic elements of the middle Adriatic region.

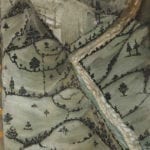

The depicted landscape. Special mention goes to the backgrounds pictured in the sacred scenes, civic narratives, and local hagiography. Only seemingly relegated to a supporting role, they actually declare the artists’ self-awareness in the representation of the space they move through, with a particular focus on the depiction of the natural environment. This sensibility also derives from the overwhelming presence of nature in this terrain, whose undulating landscape is ideally reflected in the paintings in the churches in and around Amatrice. By inserting urban views and sacred stories into the context of fields, pastures, and mountains, the artists of the Apennine valleys offer a snapshot of the environmental microcosm that is the backdrop of their work—an environment that is enlivened by a precise description of the fauna, as the animals are the natural complement of humankind in the rural society witnessed by these images.

Photographs of the catastrophe

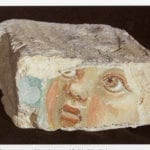

Stone-by-stone recovery and the role of photography. The reconstruction of the damaged cultural heritage according to the principle “where it was and how it was” depends on two crucial conditions: the physical preservation of the fragments, and the presence of graphic and photographic documentation of the places before the seismic event. At present, the measures for the removal of the rubble from Amatrice’s historic center have guaranteed the preservation of isolated architectural fragments—in storage rooms provided by the government department responsible for monuments, historical buildings, and the environment (the Soprintendenza Archeologia, Belle Arti e Paesaggio for the provinces of Frosinone, Latina, and Rieti)—but the rest of the urban structure shattered by the earthquake is in heaps of irreparable fragments, waiting to be sorted and disposed of as waste, to make way, gradually, for the desolate open ground where the original road layout can hardly be recognized.

Given that much of the substance of the historical center has been lost, the principle “where was it and how it was”—often misused in recent debates about reconstruction—no longer applies in the case of Amatrice; this leaves open questions about the future use of the fragments that escaped demolition.

Before Amatrice: earthquakes and photography in Italy in the 20th century

The recovery of what the earthquake damaged and the consequent reconstruction by anastylosis (reassembling the original fallen parts as far as possible) had many Italian precedents in the 20th century, but the timing and outcome of these interventions have always depended on the ubiquity and exhaustiveness of the documentation done in peacetime. But that’s not all. Whenever the extent of a catastrophe left no chance of recovery, photography offered the final act of preservation: the transmission of the memory of what had vanished. These two directions shaped the role of photography in a seismic emergency: as a tool for reconstruction and as documentary testimony.

Reggio and Messina, 1908: photography before and after. One year after the catastrophic 1908 earthquake in Calabria and Sicily, the Società Fotografica Italiana (the photographic society) published an illustrated album, Messina and Reggio before and After (Messina e Reggio prima e dopo), with images of the art-historical heritage of the two centers, images chosen from the Brogi and Alinari collections and from the Archives of the Gabinetto Fotografico Nazionale (the governmental photographic institution) accompanied by photographs of the damage shot by professional photographers or donated by military archives. The preface, by Ugo Ojetti, clarified the task entrusted to photography: “By collecting hundreds of photographs of the destroyed cities—collecting them in an orderly way and fixing them firmly in this volume—we wanted to save the destroyed cities from a second death: oblivion.”

The potential of photographic documentation to recover objects buried under the rubble and to define the extent of the loss was also grasped by the peripheral bodies responsible for the protection of cultural heritage. Despite the organizational difficulties of the still-young administrative structure, the local office for the conservation of Sicily’s monuments (the Ufficio Regionale per la Conservazione dei Monumenti della Sicilia) immediately produced analytic lists of photographs of Messina’s monuments, supplementing the images they owned with others taken by professional photographers active on site.

Marsica, 1915: the photographic campaigns of the Gabinetto Fotografico Nazionale for the city’s reconstruction. After the Marsica earthquake, the detailed photographic campaign—which accompanied a list of monuments of national interest that had been requested by the directorate of antiquities and fine arts (the Direzione Generale Antichità e Belle Arti)—constituted a precious base of information for planning the initial emergency operations. The supervising art historian Achille Bertini Calosso, among the first to intervene at the disaster sites, immediately underlined their operational value: “since the situation seems timely, I would like to note the immense usefulness of these Lists for the recovery of objects among the ruins of the buildings in the areas hit by the earthquake; this work will help us to proceed with the utmost alacrity possible.” The photography too was radically transformed as a result: it abandoned the aesthetic gratification of catastrophe in order to document the damage as a tool for reconstruction. In the church of San Pietro in Alba Fucens, the images that had been commissioned by the Gabinetto before the earthquake pointed the way for the initial emergency operations and contributed, years later, to the restoration of its 13th-century appearance with a daring and esteemed anastylosis operation.

Friuli, 1976: Venzone and “the stones of scandal”. In the small town of Venzone, destroyed by an earthquake and held up afterwards as a symbol of reconstruction done “where it was and how it was,” the rubble was recovered thanks to the community’s strenuous opposition and to the accurate graphic and photographic documentation of the urban fabric. Before the two tremors, the historic center had been the subject of a building survey and an analytical profiling, accompanied by photographic documentation, by the government office (the Soprintendenza) of Trieste. The material—together with the research by Guido Clonfero, honorary inspector and a great local connoisseur, and Hans Foramiti’s photogrammetric survey of the building elevations—was made available to technicians and designers in the municipal photo archive (the Archivio Fotografico Comunale). In the event’s aftermath, the Gabinetto, under Oreste Ferrari’s guidance, did an extensive photographic survey of the damaged sites: 2,500 shots that helped to plan and direct the reconstruction work.

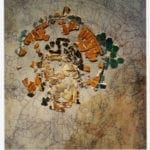

Umbria and Le Marche, 1997: Assisi and the “Utopian construction site”. The 1997 earthquake in the Apennines, across Umbria and Le Marche, compromised a whole cultural entity of many villages, parish churches, and rural chapels. But the image of the event was catalyzed by the collapse of two vaults of the upper basilica of San Francesco in Assisi, which caused the death of four people and the loss of much precious heritage of Italian painting. Despite the apparent irreversibility of the damage, a decision was immediately made to rescue the rubble, pending the establishment of procedures and the feasibility of a restoration. More than 300,000 pictorial fragments, some tiny, were collected, which left open the possibility of re-attaching them with absolute respect for the authenticity of the material. All this was possible thanks to the photographs taken before the earthquake and printed at full life size, which allowed the recomposition of the fragments, identified according to their location in the collapse and on their chromatic details.

Amatrice in black and white

It’s rare to find historical photographic documentation of cultural heritage that lies on a town’s periphery; such documentation concentrates mainly on the most representative monuments and is largely the result of particular initiatives and occasions such as exhibitions, publications, or restorations. The recurring subject of photography around Amatrice is usually the surrounding mountain landscape. Thanks to the publications of the Touring Club Italiano, the Monti della Laga peaks and the Amatrice basin became a destination for nature excursions in the 1950s.

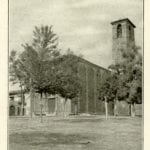

“The superb natural spectacle of the lands around Amatrice” is the phrase introducing La Conca Amatriciana (The Amatrice Basin), a 1955 documentary by Franco Romani about Giovanni Minozzi, the founder of the Opera Nazionale per il Mezzogiorno d’Italia and promoter of the first great branch location of this institution in Amatrice, in 1919. The documentary illustrates the territory of Amatrice and lingers on the churches of Sant’Agostino and San Francesco, which had both just been restored by the regional Superintendence (the Soprintendenza ai Monumenti del Lazio).

Efforts by the entities for protection and research. The most exhaustive photographic collection on Amatrice’s cultural heritage dates from the same years and stems from the intense efforts of the Soprintendenza ai Monumenti del Lazio in its two chief protection activities here: restoration and cataloguing. These images are firmly and exclusively for documentary purposes, and they are very valuable in the current post-catastrophic context because they attest to critical states of preservation and restoration operations that have, over many decades, contributed to delineate the specific vulnerability of each monument.

The restoration—done at the end of the 1950s by the regional authority for galleries and for medieval and modern artworks (the Soprintendenza alle Gallerie e alle opere medievali e moderne per il Lazio)—had the advantage of sparking fresh interest in local art among the critical community. The rediscovery of the frescoes on the occasion of the renovation led to the study of new links between local painters and the figurative school of Umbria and Le Marche. Two shots (below) by the German photographer, archaeologist, and art historian Konrad Helbig, dated 1965 and dedicated to the frescoes in Sant’Agostino and San Francesco (photographs that are now in Germany’s Bildarchiv Foto Marburg), seem to spring from an extension of Helbig’s research on Umbria (published in Umbrien. Landschaft und Kunst or Umbria. Landscape and Art), reaching beyond regional borders and into Abruzzo and Lazio.

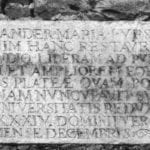

But back then, only San Francesco and Sant’Agostino attracted scholars’ attention, along the lines indicated in 1928 by Carlo Ignazio Gavini in his Storia dell’Architettura abruzzese (History of Abruzzese Architecture), where the two monuments, immortalized in four photographs (below), bear witness to the forms of late medieval architecture at the far edge of Abruzzi. Amatrice lay within the regional borders of Abruzzi until 1927, when it became part of the newly-established province of Rieti, in the region of Lazio; since then it has been under the territorial authority of Lazio’s Soprintendenza alle Gallerie e alle opere medievali e moderne (the Superintendence of galleries and of medieval and modern works).

In 1957 the sitting Superintendent Emilio Lavagnino organized an exhibition of artworks from the 11th to the 17th centuries (Opere d’arte in Sabina dall’XI al XVII), with a wide selection of the restorations that had been done in the province of Rieti. The area of Amatrice was represented by the church of Sant’Agostino, where a building reinforcement operation by the Soprintendenza ai Monumenti del Lazio had revealed the frescoed niches. Also included were other churches in the surrounding area, such as Sant’Antonio Abate in the village of Cornillo Nuovo, San Giovanni in the village of Prato, the Icona Passatora in Ferrazza, and Santa Maria della Filetta, all of which were in a precarious state before the operations of reinforcement, roof reconstruction, and fresco restoration.

The 1957 exhibition was followed in 1966 by another one, on artworks in Sabina that had been restored by Lazio’s Superintendence of monuments and galleries (the exhibition was Opere d’arte restaurati in Sabina dalle Soprintendenze ai Monumenti e alle Gallerie del Lazio), which similarly aimed to “broadly sketch the program executed by the Superintendence of Monuments and Galleries.” As the introduction to the catalogue said, “Many works that were hardly recognizable have been made visible; threatened works have been restored; many masterpieces have been brought back to their previous splendor; many paintings regained their purity of style and color.” The Superintendence was busy in those years, as can be seen in the historical archive, in the photographic collection dedicated to the structural reinforcements, to the reconstructed roofs, and to the discovery and restoration of many frescoes—all operations coordinated by the inspector Luisa Mortari.

From the end of the 1960s, moreover, the entire province of Rieti was extensively catalogued. This survey of the “lesser” cultural heritage had been partly begun already, years earlier, by Luisa Mortari in collaboration with Italo Faldi. The Superintendence archives still have—alongside the files and photographs of the artworks of the major monuments in and around Amatrice—an exhaustive catalogue of the movable heritage of religious buildings and of the sculptural decorations of civilian buildings, now wrecked by the earthquake and the initial post-emergency operations.

The Superintendence’s commitment to safeguarding the broader entity of the town’s cultural heritage (both great and minor) was reaffirmed in 1979, when it launched a campaign to survey the damage to Amatrician monuments from the 1979 Valnerina earthquake; traces of this remain in its Historical Photographic Archive.

The photographs (below)—documenting cracked walls, disarray, and spots where the paint has crumbled away in the church of the Purgatory and the churches of Santa Maria delle Grazie, San Giovanni, and San Martino—are the most persuasive evidence of a seismic history that was neglected because these sites seemed peripheral to the epicenter of the earthquakes of 1979 and 1997. This minor damage was not addressed; over time, it worsened the overall state of Amatrice’s buildings.

Hutzel and the “minor heritage” (1968). Max Hutzel ran a project, Foto Arte Minore (Photographs of Minor Art), from the late 1950s until 1988, which focused on the minor towns overlooked by Superintendencies and art historians. Hutzel explained the aim of his project in a 1982 letter to George Goldner: “Around 30 years ago, I discovered that the private and state archives in Italy had collected photographic material on only the largest museums and cities, the most famous palazzi and churches … the world-famous painters, sculptors and architects. Nobody had realized that, away from the big streets—in the valleys and mountains—you find thousands of small cities and villages—nearly forgotten ‘by God and man’—where handcrafted art was born. Right here, in these unknown villages, you can find the cradle, or the source, of all Italian art. The art produced in these small centers helped to train the most famous artists, the ones that everyone still talks about (unfortunately only about them). My collected material modestly aims to provide proof that these unknown works of art, hidden away in remote villages, are no less considerable or less important. Unfortunately, a large portion is already lost and is moving closer every day towards degradation and destruction.” Hutzel took more than 30 photographs of Amatrice, of the church of San Francesco and its mural paintings.

What remains

Since August 24, 2016, Amatrice has been in constant transformation: the devastation of the earthquake, the emergency operations, and the removal of the rubble, but also the installation of temporary housing modules have—over and over—created new and ever-changing scenarios that deserve to be documented. Thus the Fototeca Hertziana decided that the nucleus of historical images owned by the Fototeca—drawn partly from the archives of the Superintendence (the former Soprintendenza ai Monumenti del Lazio), and partly from campaigns done right after World War II—should be supplemented with present-day photographs documenting the current transformations. Hundreds of digital photographs were acquired, which had been taken by the photographer Giovanni Lattanzi at the earthquake’s epicenter; at the same time, the Fototeca Hertziana commissioned its photographer Enrico Fontolan to do periodic photographic campaigns.

The time sequence documented by these collections serves as a gradual monitoring of the dynamics set in motion by the earthquake, and contributes to building a visual chronicle of the affected places and their transformations. It is a kind of diary of images for the people who will reconstruct the city, like what the historian and philologist Augusto Campana wrote about (in a different context of devastation) in his war diary Le pietre di Rimini (The Stones of Rimini): “to keep alive the memory of how much happened, again and again, that touched on the archaeological, artistic, and historical heritage of the city, with the principal goal of offering valuable data for whose who will have to deal with the restoration or the study of the monuments, and the historical material in general.”

Through photography, it is possible to trace the signs of change happening in Amatrice: the project, in that sense, will continue to grow through the periodic updates on location and will offer all the collected photographic material here online.

The series of images (above) of two towers—the bell tower of Sant’Emidio and the Torre Civica—documents the varying conditions of monuments in the accelerated reality of the city after the catastrophe. Their soaring shapes, bent and then decapitated and then wrapped in safety frames, are now prominent landmarks, the only vertical markers of the material memory of the city after its destruction.

Vulnerability. The images from recent photographic campaigns, when compared with historical photographs, provide a basis for outlining the story of the preservation of Amatrice’s principal monuments: the Torre Civica and the churches of San Francesco, Sant’Agostino, and Sant’Emidio (which housed the museum, the Museo Civico “Cola Filotesio”). In the case of these buildings, the simple juxtaposition of historical photos (from the 20th century) with recent pictures shows clearly the preexisting deterioration, as well as the restorations and the modifications that inevitably occurred through the years. At the same time, the photographic evidence contributes to an understanding of the mechanisms of the damage triggered by the earthquake and the identification of the best counter-seismic measures.

In the sequence dedicated to the façade of San Francesco (above), the pictures document the heightening of the façade during the 1950s restoration and the façade’s collapse in the earthquake of August 24, 2016, which worsened a crack that was already seen in the historical photos. The images made in 2017 and 2018 show new signs of decline caused by the continuation of the tremors and amplified by the loss of the roof, with consequent injury by atmospheric agents (problems that are now partially halted, thanks to better security).

A similar process can be reconstructed in the façade of Sant’Agostino, which was also heightened in the 20th century, with the opening of its rose window. In this case, too, the renovated portion was the first to falter under pressure from the tremors. Recent images testify to both the progression of the damage after the earthquake of October 30, 2016, and also the amplification of the seismic effects, as seen in the tower. The first tremors, which triggered the collapse of the adjacent city gate (the Porta Carbonara), highlighted the relationship among three elements—the tower, the gate, and the church. Later on, the tower, visibly tilted during the long shudders of the earthquake, crumbled on January 18, 2017, shortly before the security operations were supposed to start (operations troubled by the protracted tremors and the particularly cold and snowy winter).

Dislocations. The debate on the ruins from calamities—whether natural or man-made—has gained particular notice in recent publications, signaling a new interest in the field of emergency measures for the removal and selection of rubble. The tremors that hit Amatrice in 2016 and 2017 prompted preservation technicians at the national level (in the Istituto Superiore per la Conservazione e il Restauro) to establish specific procedures for the removal and recovery of rubble from protected assets and historical buildings (“Procedure per la rimozione e il recupero delle macerie di beni tutelati e di edilizia storica”). These procedures are based on a distinction among three categories of material—(A) rubble from protected heritage, (B) remains of historic buildings, and (C) material with no cultural importance—which permits crews to separate recoverable fragments from the material that can be trucked to landfills.

The pictures (above and below) illustrate the debris-clearing operations, with the rubble being selected as it moves along a conveyor belt, and the different materials heaped in distinct piles. As it was urgent to restore access to the Corso for emergency vehicles, the rubble cluttering the street had to be removed and transported to a storage space in the quarry of Albaneto, near Posta, thus postponing the sorting of recoverable fragments. In some cases, valuable elements were found and transported to storage facilities offered by the municipalities or set up by the ministry of cultural heritage (Ministero per i Beni e le Attività Culturali).

These fragments now urgently demand a reflection on their future use, since the loss of Amatrice’s historic city center made it impossible to reconstruct the city on the principle of “where it was and how it was”; this leaves open questions about the reuse of the fragments saved from demolition. Whatever measures are implemented for the new Amatrice, it will be necessary to make use of the photographic medium in its dual role: as a testimony of the town that no longer exists, and, at the same time, as an instrument for documenting its scattered parts.

A different fate befell some of the fragments of churches and buildings of art-historical interest. This last series of photographs (above) tells the story of the portal of San Francesco, which had been restored just before the earthquake. The images show the sculptures of the splay, tumbled to the ground along with the restorers’ scaffolding posts, and then the measures to secure the walls and to sort the surviving sculptural fragments. The sculptural group from the lunette, fortunately unharmed, was rescued by the fire brigade and then exhibited in the show about the saving and “re-birth” of artworks from Amatrice and Accumoli, Rinascite. Opere d’arte salvate dal sisma di Amatrice Accumoli (Rome, 2017–2018).

What future

Already at dawn on August 24, 2016, hours after the first tremor, the mayor of Amatrice exclaimed, while raising the alarm: “The town is no more!” But despite this sudden devastation, the wounded town has not vanished completely: the rubble and fragments of the structures maintain their own physical persistence, although they have been dashed to the ground and dismembered. That is the assumption that led to the rebuilding of the historic town of Venzone, which many see as a successful example of post-seismic reconstruction in Italy. The torn, split, and scattered substance that was Amatrice survives in parts, today, in the warehouses, and it will necessarily take on new forms of use and perception. The movable heritage can be handled more easily: rescued and collected in storage facilities, it remains decontextualized and is destined for museums, as has already happened in many similar episodes of Italy’s long seismic history.

The body of the city. As we wrote this, more than three years after the start of the quakes in 2016, the rubble had largely been removed, and Amatrice had nearly vanished: its buildings, furnishings, piazze, and monuments, destroyed by the tremors and erased by the bulldozers, will remain as images—and all the more precious for it. The panoramic views shot at the end of 2018 transmit the sense of bewilderment one feels in walking through the lost urban space, where the only shadows are those cast by the two surviving towers soaring above the wasteland, as if they were archaeological remains of a lost city. In the absence of the urban structure, the mountains that previously embraced the town are now the absolute protagonists of a silent landscape where nature has regained the upper hand.

With the loss of the original urban street network and all its reference points (recalled now only by the ghostly fenced corridor of Corso Umberto), and with the erasure of the relation between “inside the town” and “outside the walls,” will it still be possible to reconstruct Amatrice?

The surviving monuments, the towers, the bits of the churches that were spared by the earthquake and the bulldozers—how will they interact with the new city that must accommodate the injured community and its daily life? Just like at the very beginning of its history in the 13th century, Amatrice will once again be a “new foundation” town.

To learn more

Due to the variety and scope of the topics covered, this digital project cannot host exhaustive bibliographical references; we hope to publish those elsewhere. For an initial examination of individual topics, we present below a selection of essential items.

For Amatrice as a centre of art and architecture before the earthquake see esp. Anna Imponente and Rossana Torlontano (eds.), Amatrice. Forme e immagini del territorio, Milan 2015, and the article by Francesco Gangemi, Ai confini del Regno. L’insediamento francescano di Amatrice e il suo cantiere pittorico, in Universitates e baronie. Arte e architettura in Abruzzo e nel Regno al tempo dei Durazzo, ed. by Pio F. Pistilli, Francesca Manzari and Gaetano Curzi, Pescara 2008, vol. 2, pp. 93–118. The earthquake has stimulated new research on the Appenine region; Alessandra Acconci has recently collected the relevant bibliography: Memoria. La civiltà degli Appennini e il patrimonio artistico di Amatrice e Accumoli, in Rinascite. Opere d’arte salvate dal sisma di Amatrice e Accumoli, Exh. cat. Rome 2017–2018, ed. by Alessandra Acconci and Daniela Porro, Verona 2017, pp. 145–147, to which should be added the articles in the recently published volume Ai piedi della Laga. Per uno sguardo d’insieme al patrimonio culturale ferito dal sisma nel Lazio, ed. by Giuseppe Cassio et al., Milan 2019.

Regarding the relation between photography and catastrophic events, there are various contributions dedicated to earthquakes in Italy in the 20th century. Paola Callegari, Fotografare le calamità. La fotografia, il territorio e i disastri naturali, in La furia di Poseidon. 1908 e 1968: I grandi terremoti di Sicilia, ed. by Giovanni Puglisi, Paola Callegari, Milan 2009, pp. 9–17; Valentina Valerio, Gli scatti del tempo puro. Il ruolo della fotografia nella ricostruzione della chiesa di San Pietro ad Alba Fucens danneggiata dal terremoto del 1915, in Storia dell’arte come impegno civile. Scritti in onore di Marisa Dalai Emiliani, ed. by Angela Cipriani, Valter Curzi, Paola Picardi, Rome 2014, pp. 267–274; La memoria di un evento. Il Friuli terremotato nelle immagini del gabinetto Fotografico Nazionale, ed. by Floriana Marino, Trieste 2014; Tiziana Serena, Catastrophe and photography as a “double reversal,” in Wounded cities. The representation of urban disasters in European art (14th–20th centuries), ed. by Marco Folin and Monica Preti, Leiden 2015, pp. 137–164.

The historic images relating to various sources and uses (heritage, historiography, tourism) play an important role when narrating the history of the region and the monuments of Amatrice. Our research has relied on many photographic archives, and a number of images from the Soprintendenze Archeologia, Belle Arti e Paesaggio have been published in the meantime in the volume Amatrice con gli occhi di prima, Fondazione Dino ed Ernesta Santarelli, Cinisello Balsamo 2019.

The contribution of photography to the analysis of the vulnerability of monuments is a subject too vast to be treated here. We hope for a renewed exchange with other disciplines such as architecture and civil engineering; here we cite only the rich essays by Francesco Doglioni, starting with his pioneering Le Chiese e il Terremoto. Dalla vulnerabilità constatata nel terremoto del Friuli al miglioramento antisismico nel restauro, verso una politica di prevenzione, ed. by Francesco Doglioni, Alberto Moretti, Vincenzo Petrini, Trieste 1994.

For the role of protection institutions in seismic emergencies, it was essential to examine the ministerial decrees and directives, as well as the guidelines introduced during the most recent catastrophic events, based on the Procedure per la rimozione e il recupero delle macerie di beni tutelati e di edilizia storica established by the Istituto Superiore per la Conservazione e il Restauro.

The research group

This project is the result of a series of reflections and initiatives developed in different contexts: a workshop, hosted by the Bibliotheca Hertziana on December 6, 2016, with the title Conversazione su Amatrice. La città e il territorio all’indomani del sisma (Conversation about Amatrice: the city and the territory in the aftermath of the earthquake), in which the present research group was formed; and Francesco Gangemi’s stay at the Italian Academy for Advanced Studies in America at Columbia University, New York (2017), where the idea for this digital exhibition was born. The project was launched by the Photographic Collection of the Bibliotheca Hertziana, which proposed an online publication, provided continuous scientific and technical support and maintained a fruitful collaboration with the territorial Soprintendenze involved.

Francesco Gangemi is an art historian and former postdoctoral researcher at the Bibliotheca Hertziana and at the Kunsthistorisches Institut Florenz – Max-Planck-Institut

Rossana Torlontano teaches History of Modern Art at the Università “G. D’Annunzio” in Chieti-Pescara

Valentina Valerio is an art historian at the Sovrintendenza Capitolina ai Beni Culturali di Roma

Idea, texts and image selection Francesco Gangemi, Rossana Torlontano, Valentina Valerio

Conception of the online exhibition Tatjana Bartsch, Francesco Gangemi, Johannes Röll, Rossana Torlontano, Valentina Valerio

Realisation web Tatjana Bartsch

Translations Charlotte Huber

Assistance Enrico Fontolan, Christian Höger, Marga Sanchez, Marlene Schwemer, Maria Tafelmeier

Photo credits Soprintendenza Archeologia, Belle Arti e Paesaggio per l’area metropolitana di Roma, la provincia di Viterbo e l’Etruria meridionale, Soprintendenza Archeologia, Belle Arti e Paesaggio per le province di Frosinone, Latina e Rieti, Bibliotheca Hertziana, The Getty Open Content Program, Bildarchiv Foto Marburg, Comando Carabinieri Tutela Patrimonio Culturale – Nucleo di Roma, Corpo Nazionale dei Vigili del Fuoco, Comando dei Vigili del Fuoco di Amatrice, Archivio Storico dell’Istituto Luce, Apple Maps, Enrico Fontolan, Francesco Doglioni, Francesco Gangemi, Giovanni Lattanzi, Antonio Ranesi, Valentina Valerio

The complete photographic campaign by Enrico Fontolan, photographer of the Bibliotheca Hertziana, of the state of Amatrice on 9.11.2018 can be viewed under this link in the online catalogue of the Photographic Collection.

Acknowledgements We are grateful to the Soprintendenza Archeologia, Belle Arti e Paesaggio for the metropolitan area of Rome, the province of Viterbo and southern Etruria and to the Soprintendenza Archeologia, Belle Arti e Paesaggio for the provinces of Frosinone, Latina and Rieti, who have made available the historical documentation preserved in their archives. We would particularly like to thank the Superintendents Margherita Eichberg and Paola Refice, as well as Stefano Gizzi, who initiated and supported the collaboration with the Photographic Collection of the Bibliotheca Hertziana.

The first impulse for this exhibition was given by the Italian Academy for Advanced Studies in America, Columbia University, New York, as part of the International Observatory for Cultural Heritage. We are grateful to David Freedberg and Barbara Faedda for their confidence in the project. Special thanks go to Abigail Asher, for her constant collaboration and commitment in the revision of the English text.

We are indebted to Mario Ciaralli, a field witness of the transformations taking place in the earthquake-stricken city.

We thank Giusi Lombardi for her contribution to the initial phase of collection and analysis of the historical photographs.

Thanks also to Carmen Belmonte, Alessandro Betori, Giuseppe Cassio, Enrico Ciavoni, Chiara Delpino, Federica di Napoli Rampolla, Valentina Milano, Regine Schallert, Elisabetta Scirocco, Salvatore Settis, and Gerhard Wolf.

1.6.2020